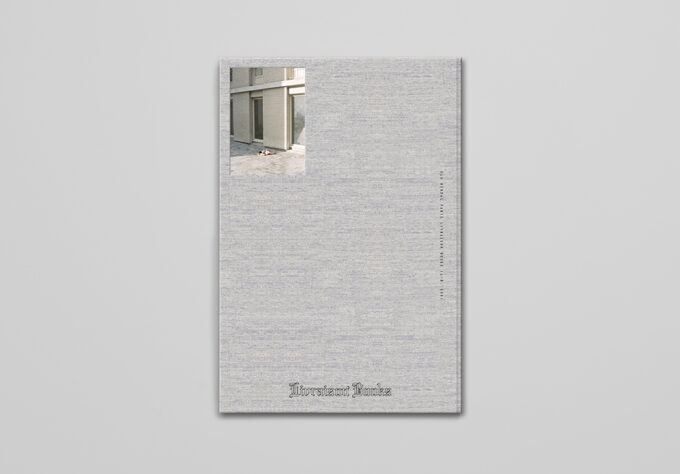

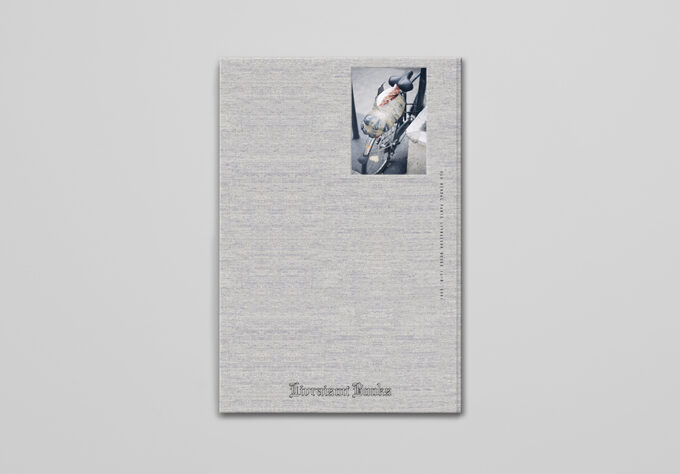

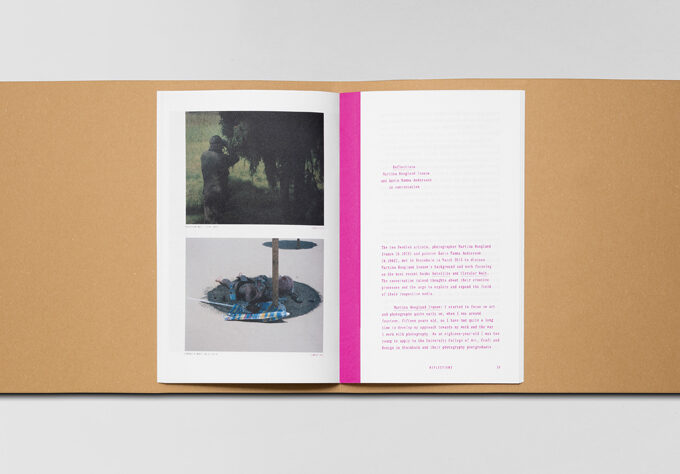

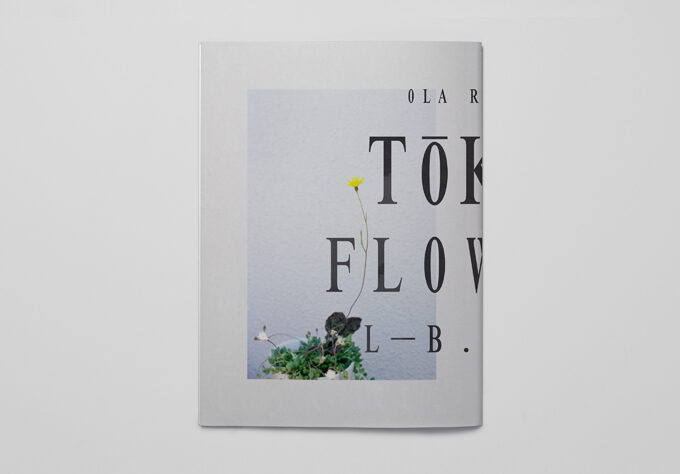

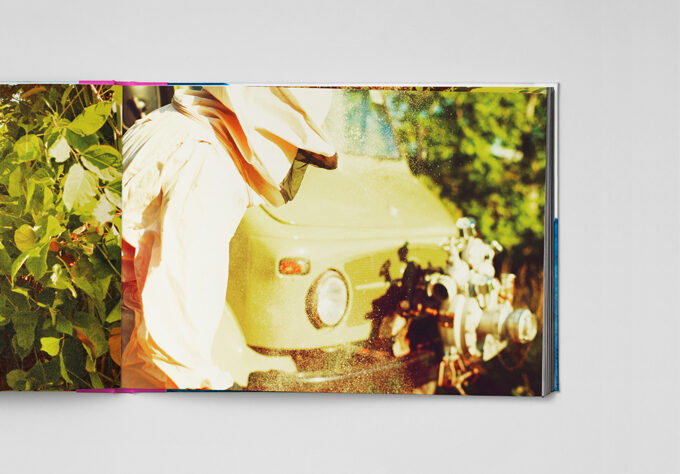

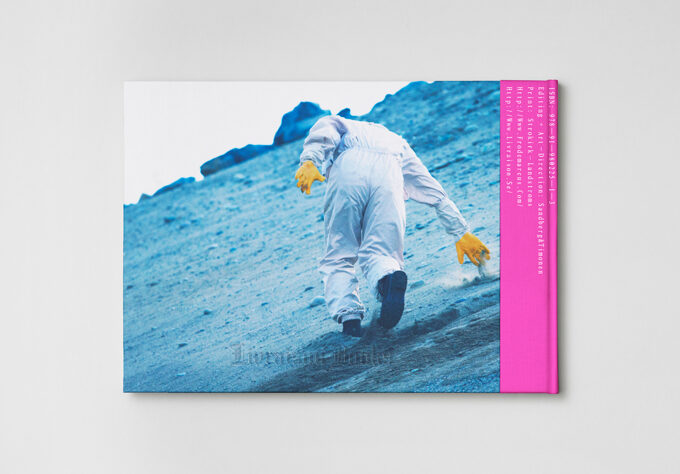

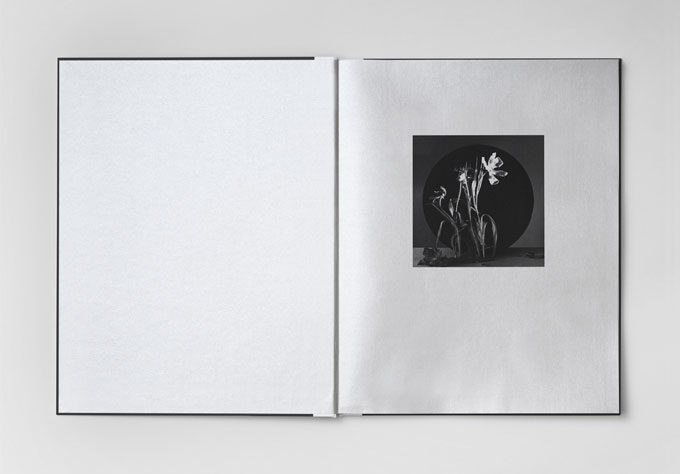

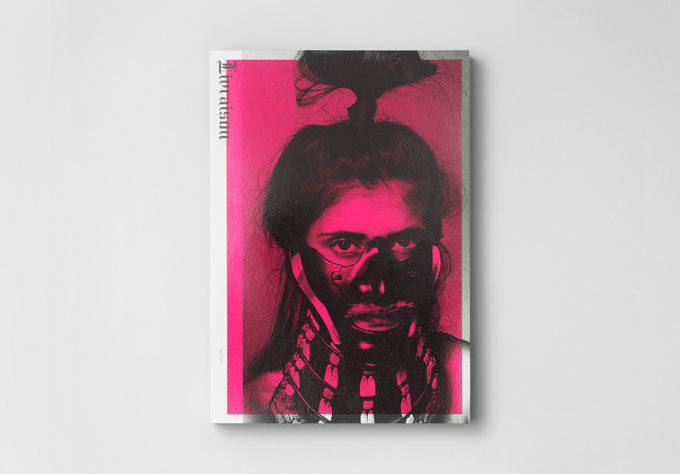

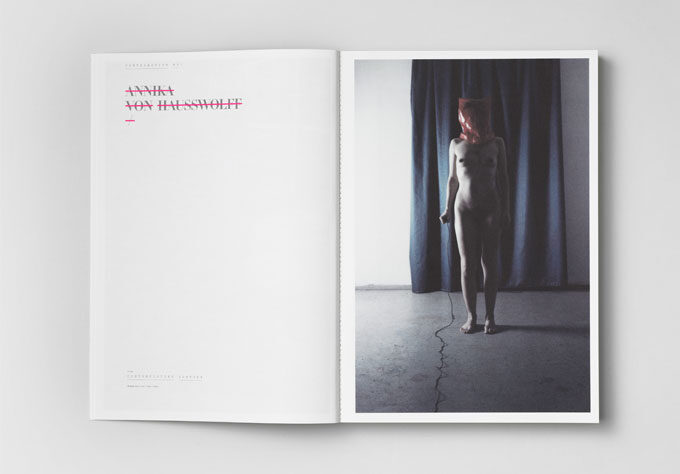

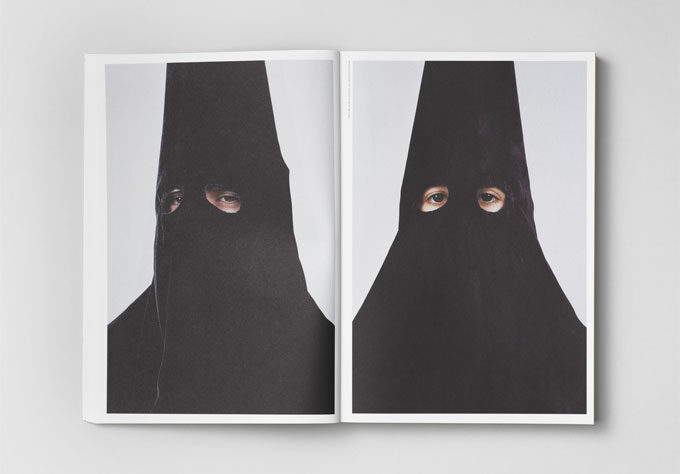

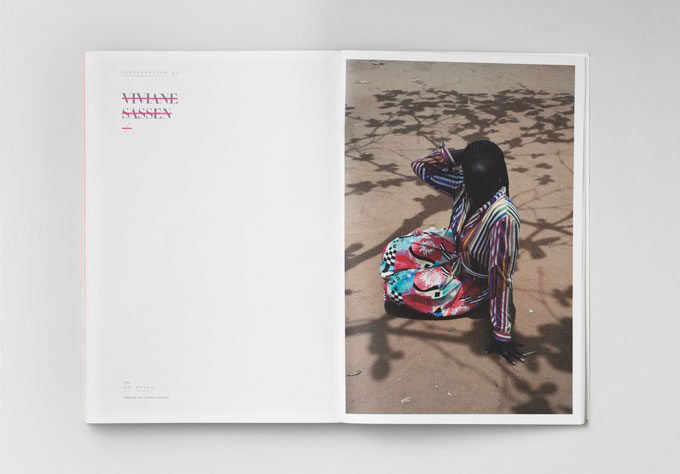

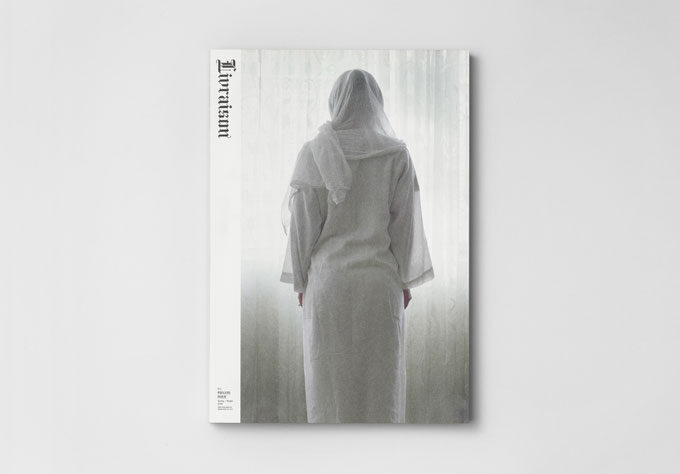

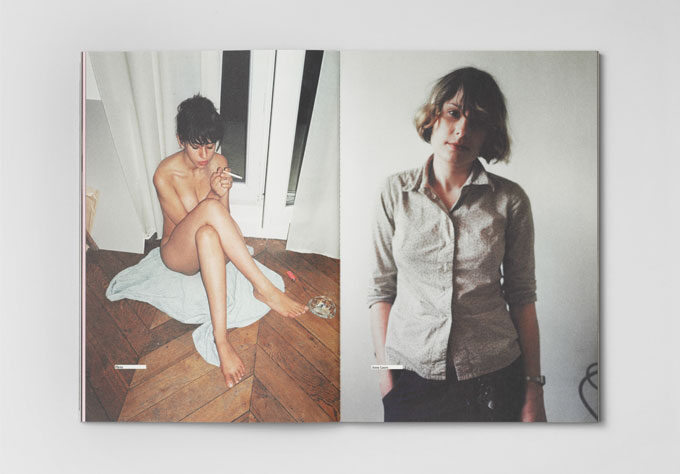

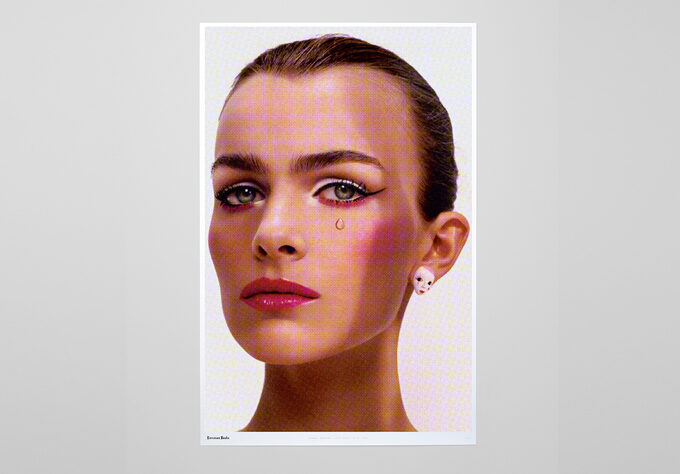

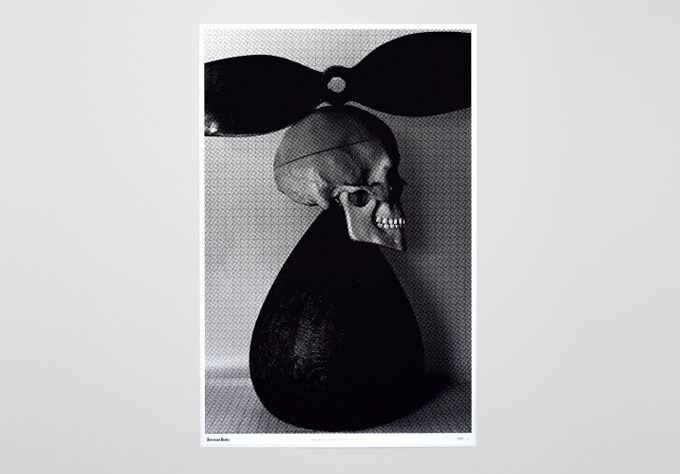

OLA RINDAL

PARIS (L—B. 009)

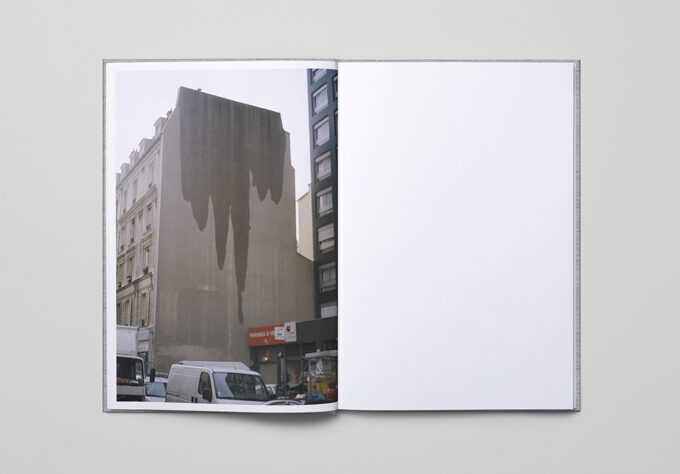

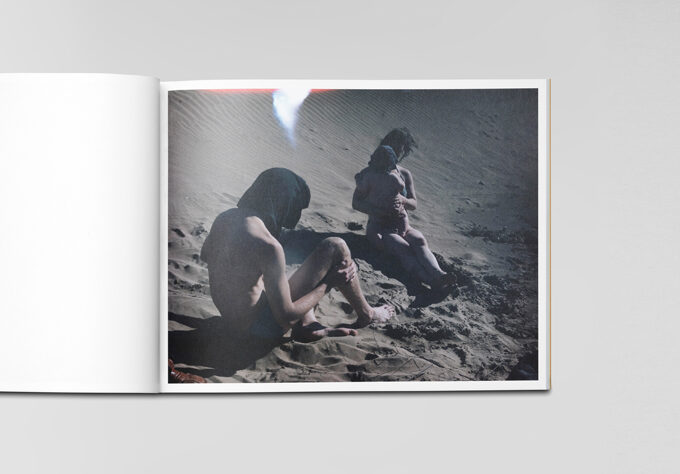

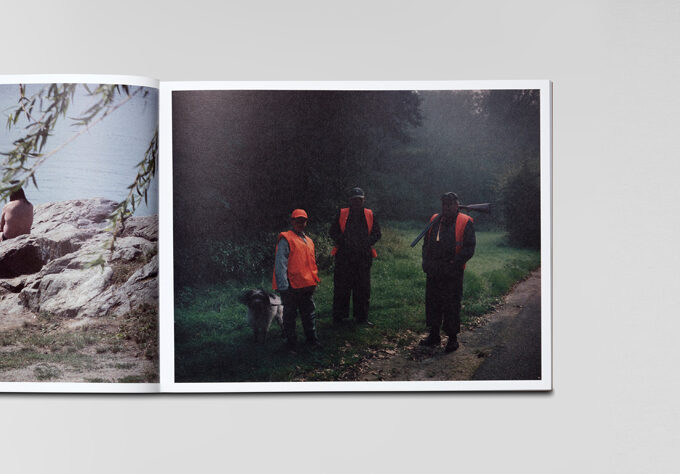

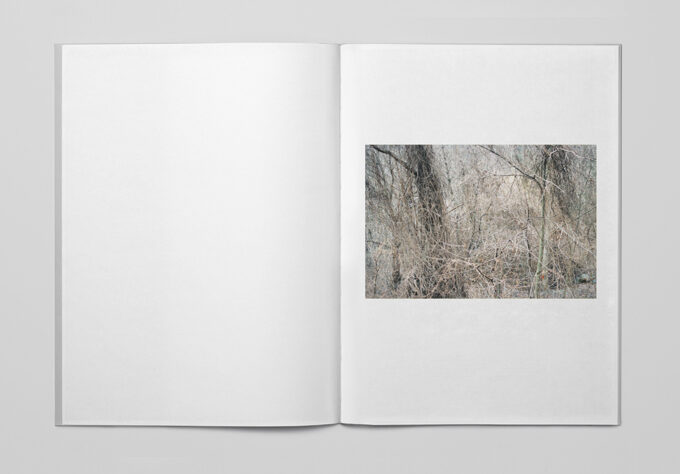

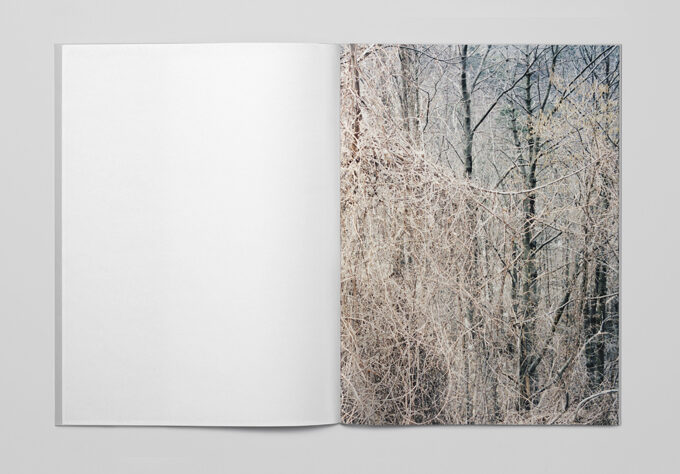

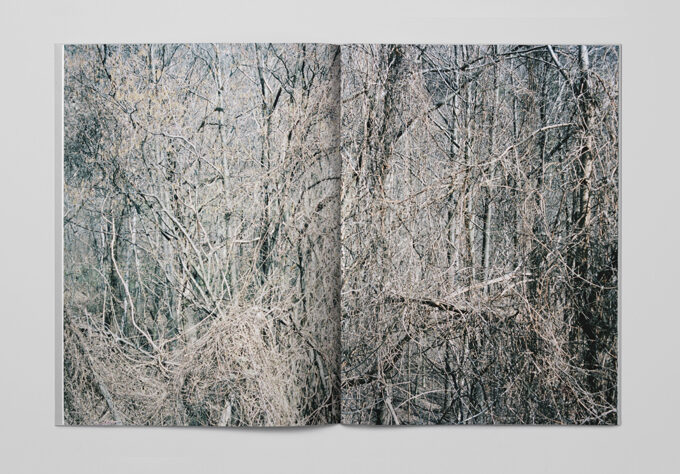

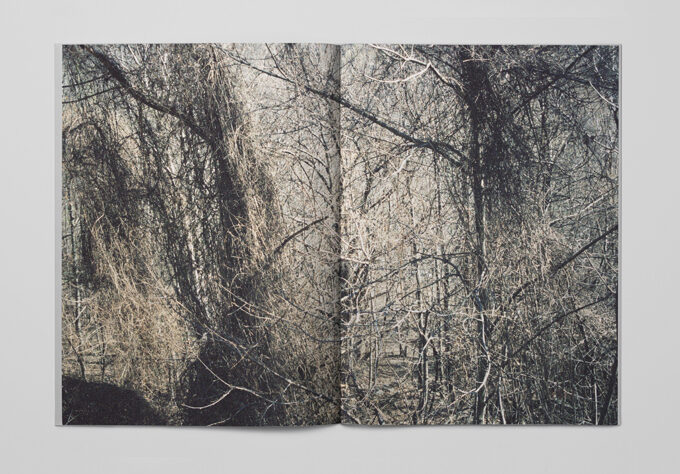

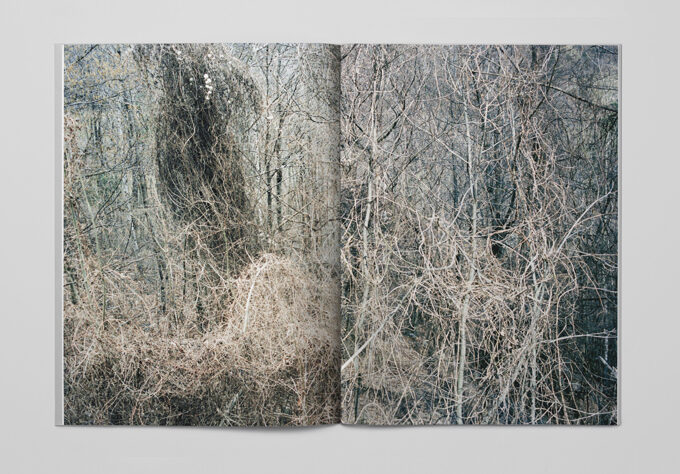

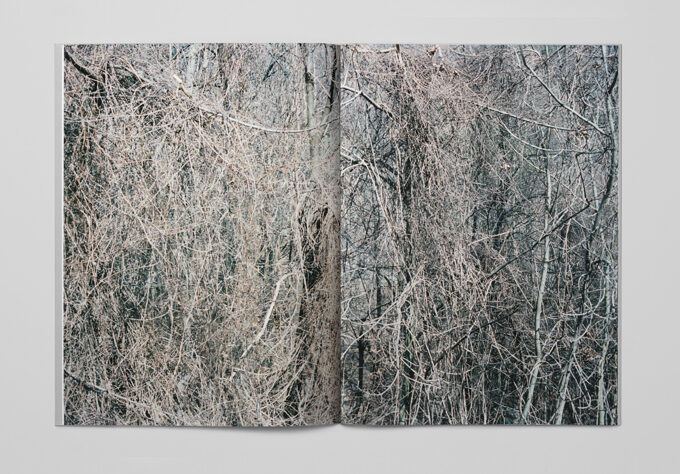

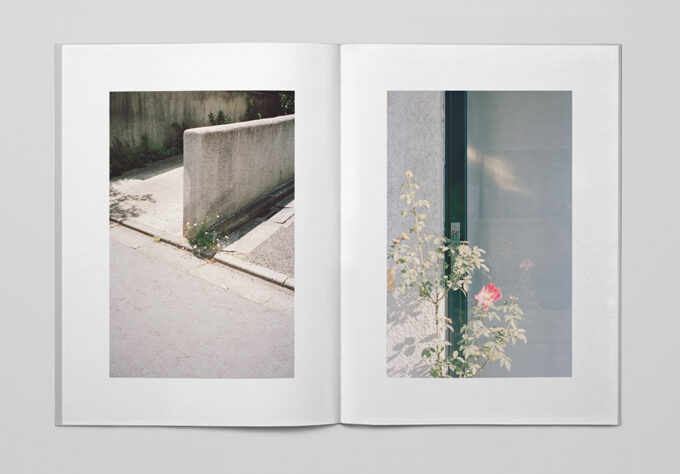

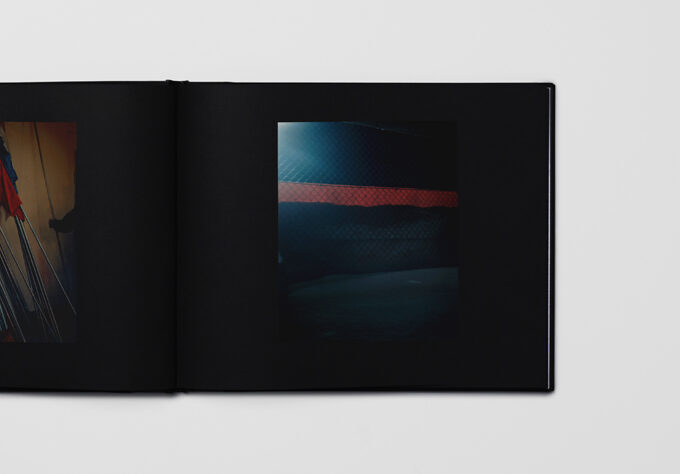

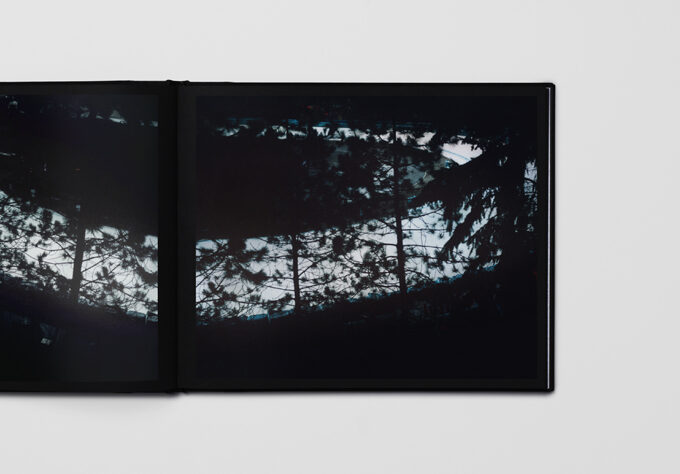

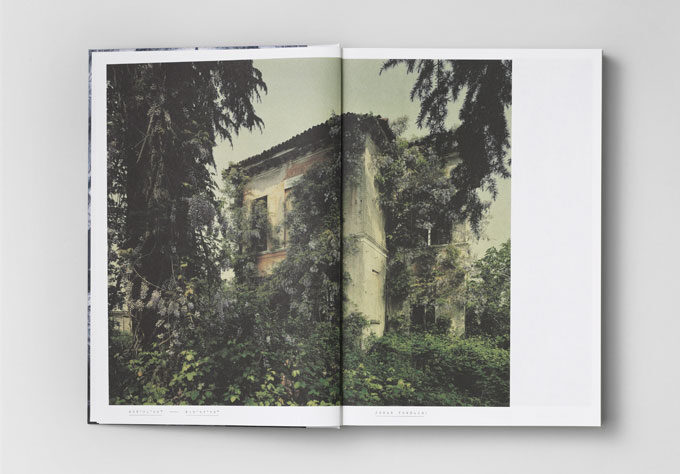

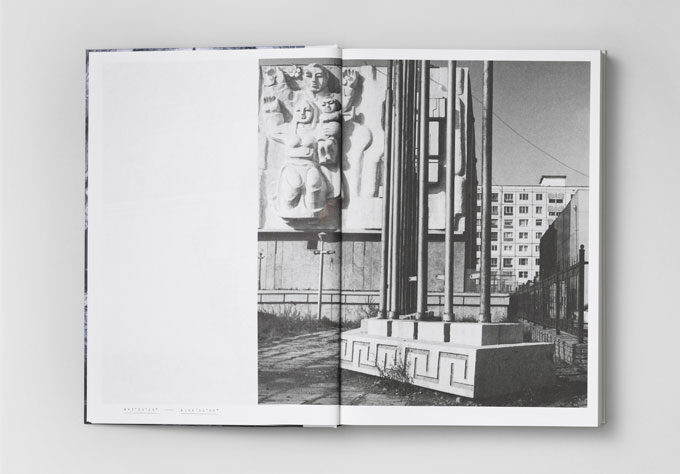

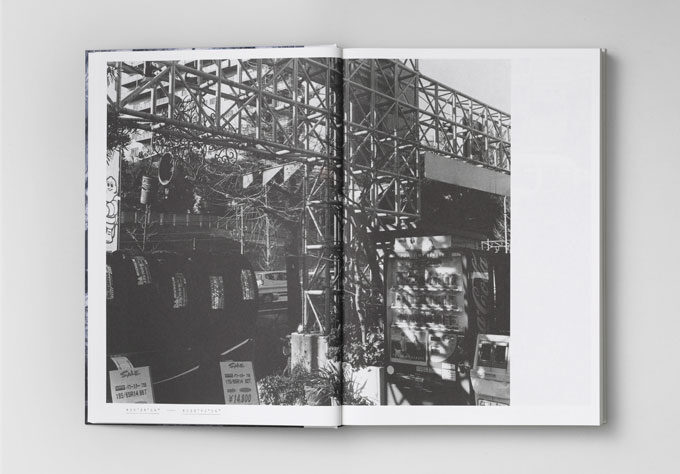

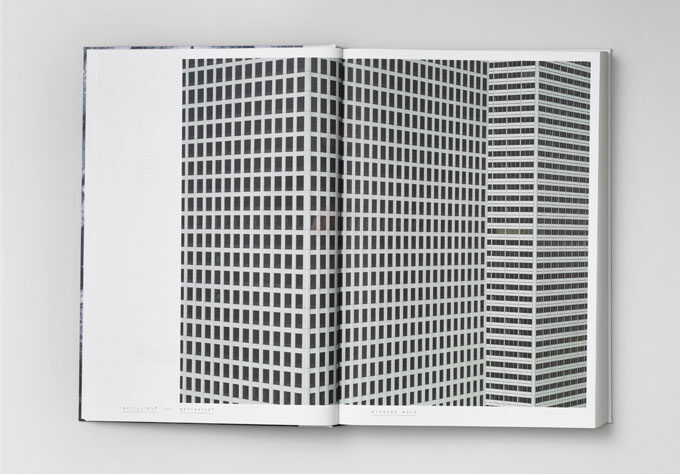

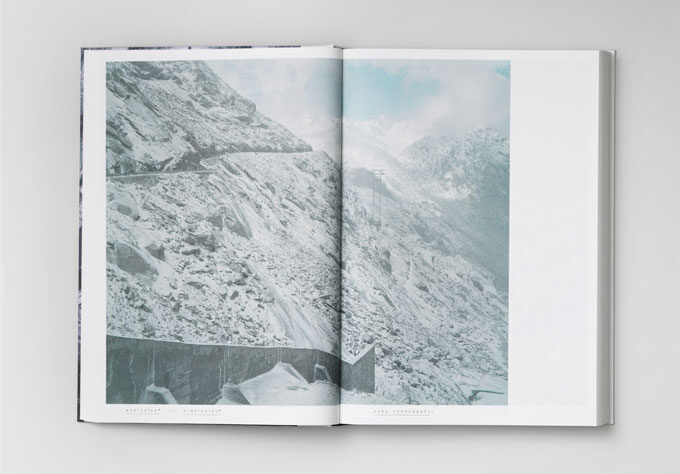

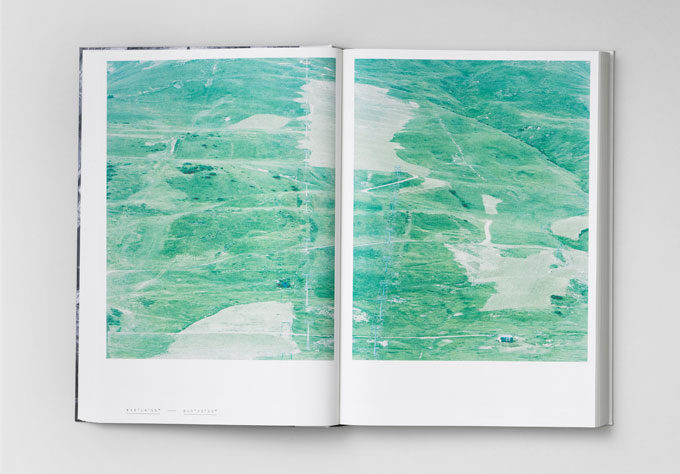

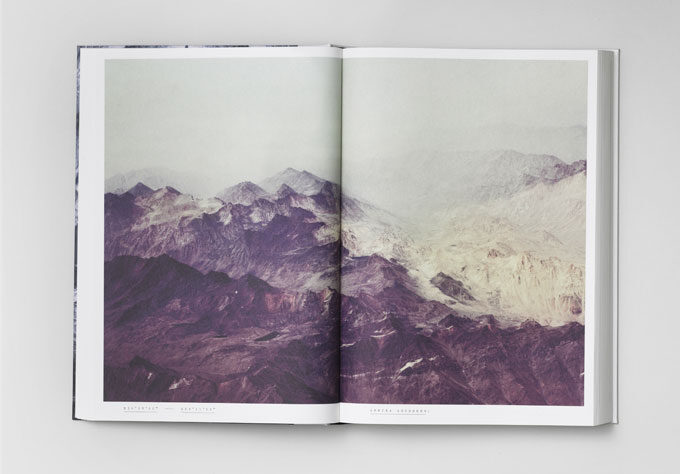

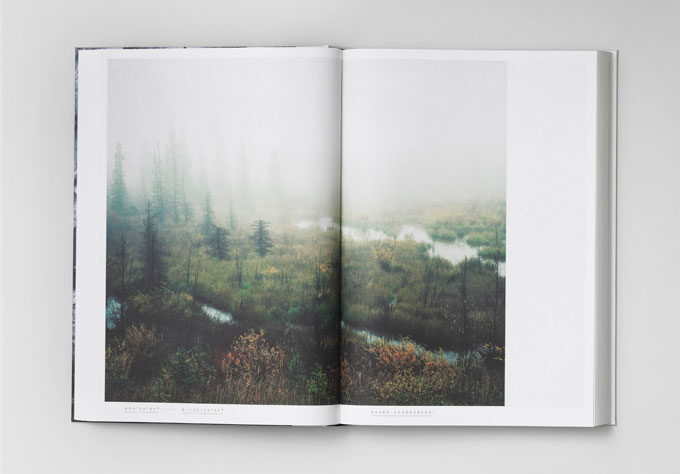

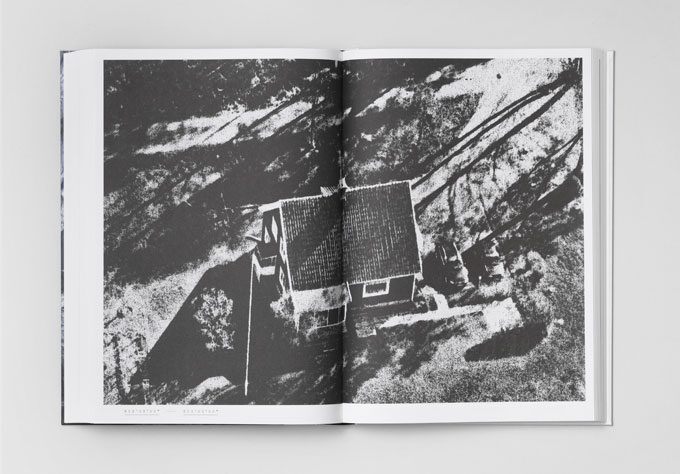

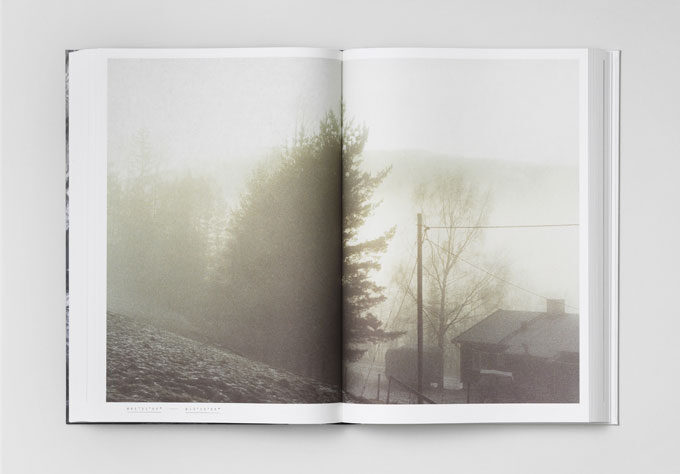

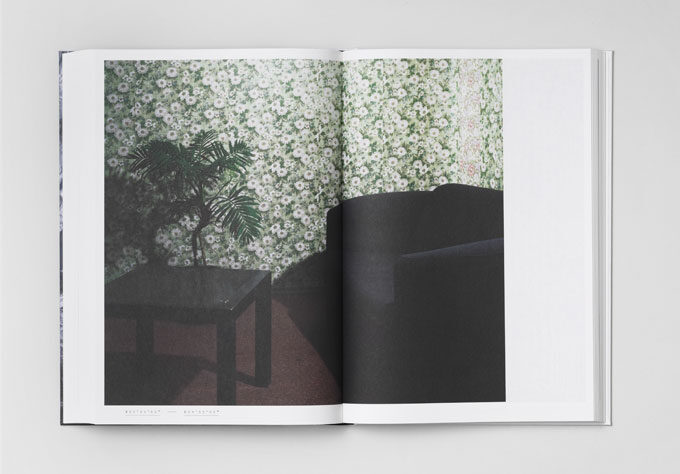

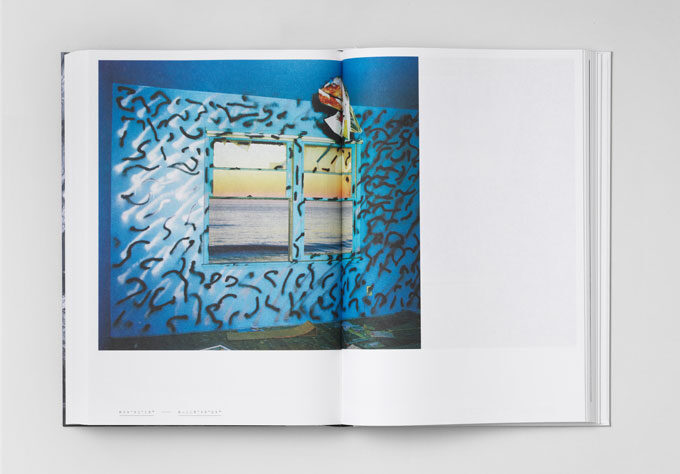

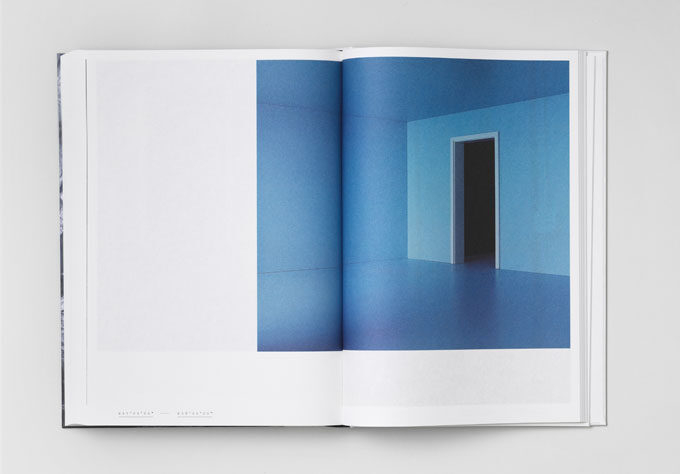

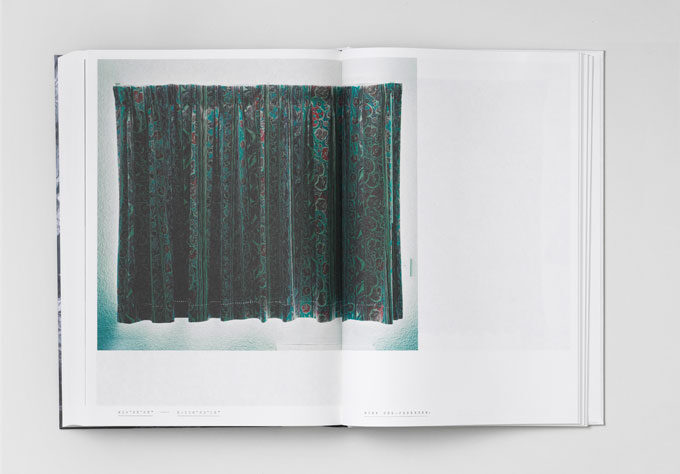

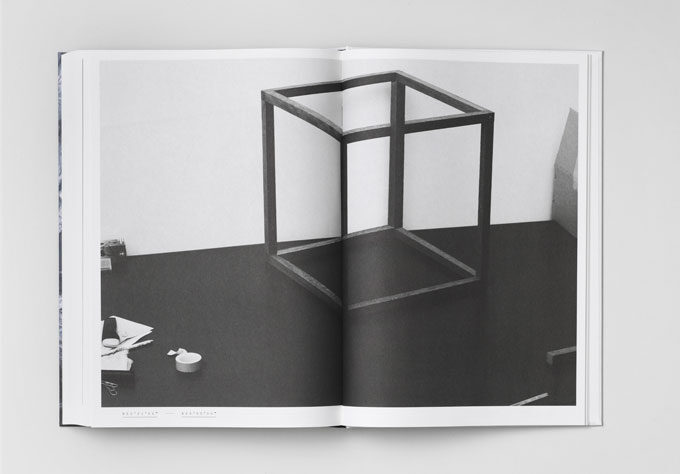

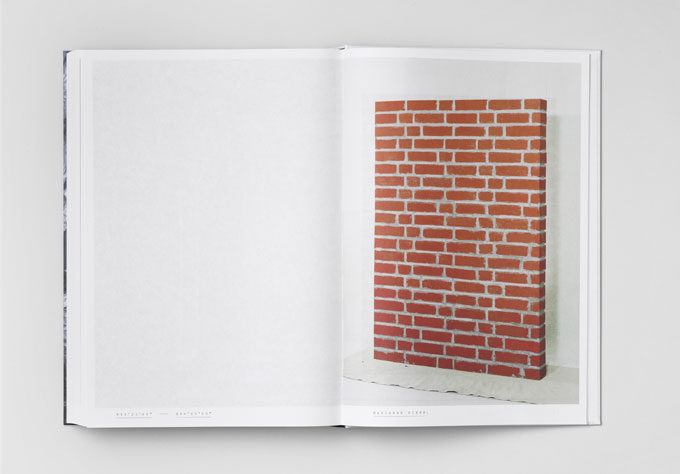

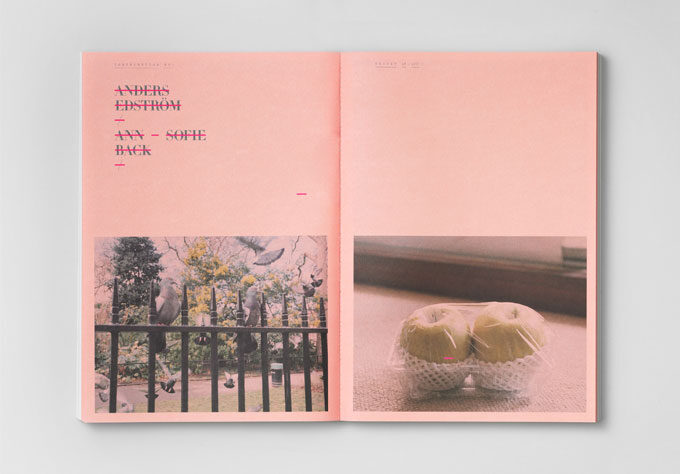

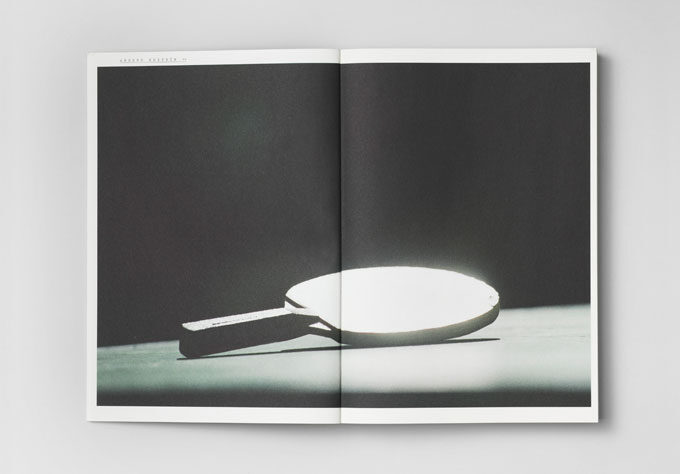

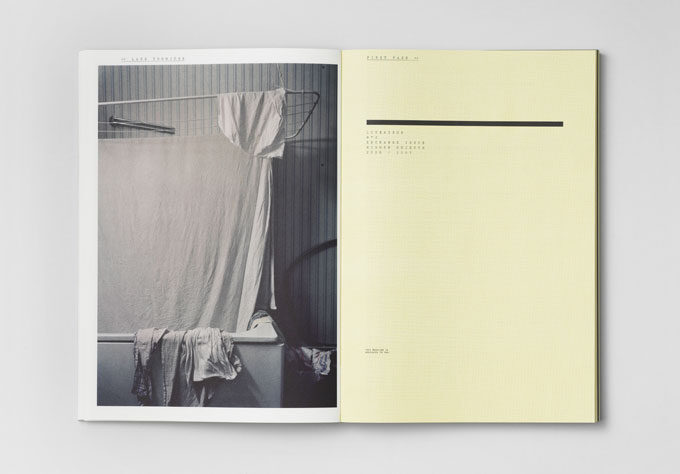

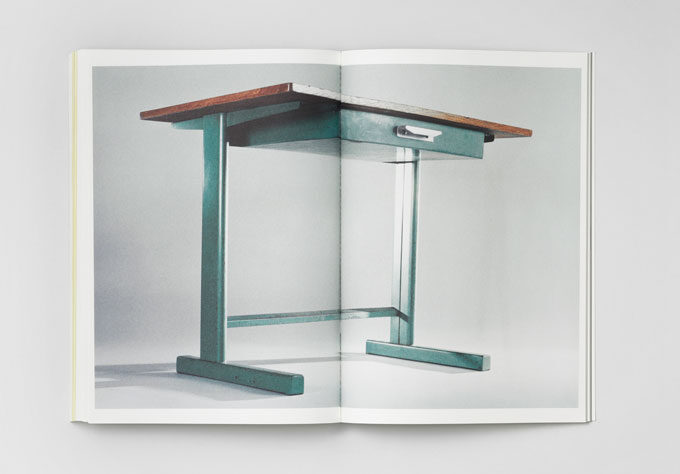

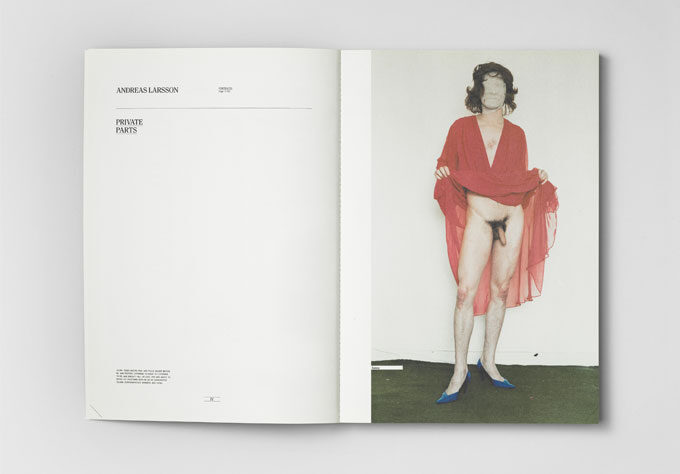

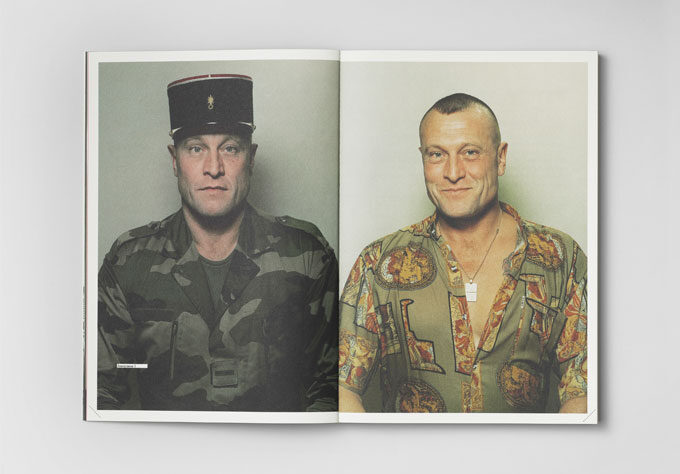

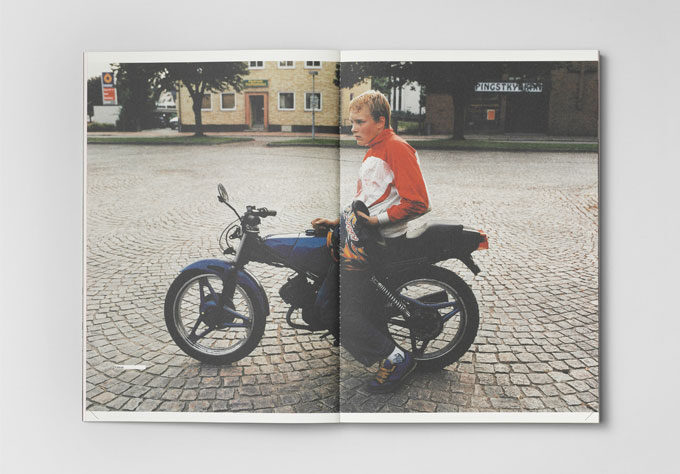

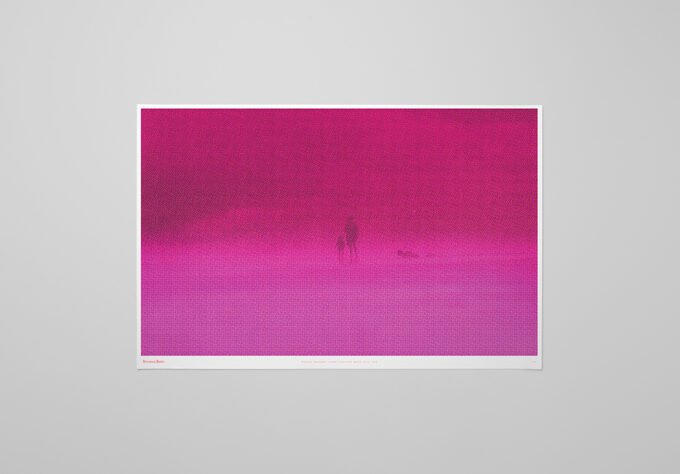

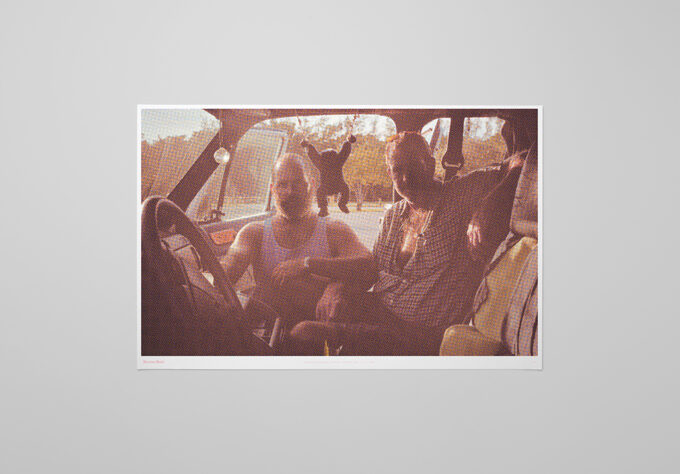

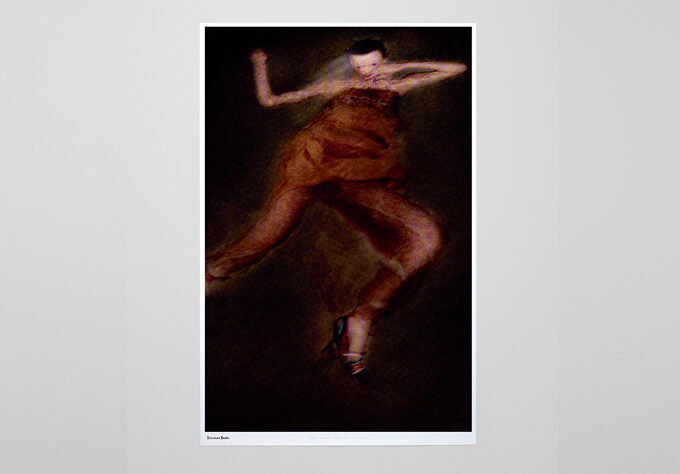

What tends to catch Ola Rindal’s eye in the »Paris« photo series is not the city’s most obvious optical attractions but the gaps in the urban fabric. His is a not a subjectively imagined Paris. It is a Paris that exists in the real world, albeit at the edge of our field of vision. Vaguely familiar but not immediately recognizable, the side of Paris that come into view here is its non-places.

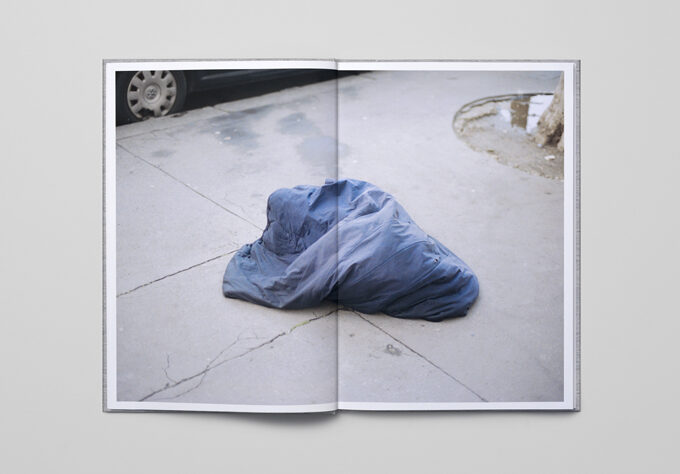

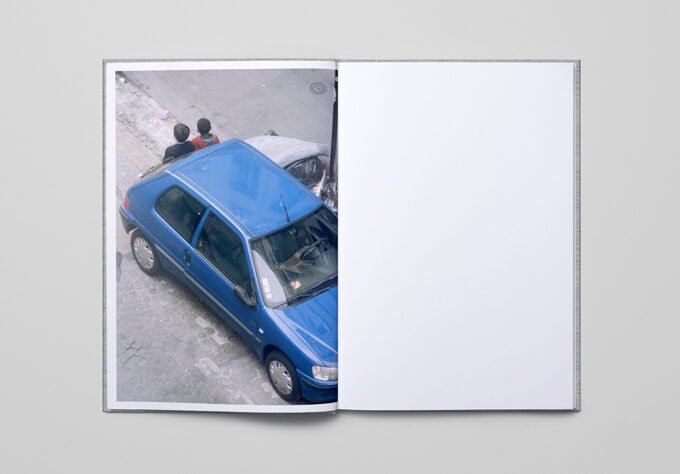

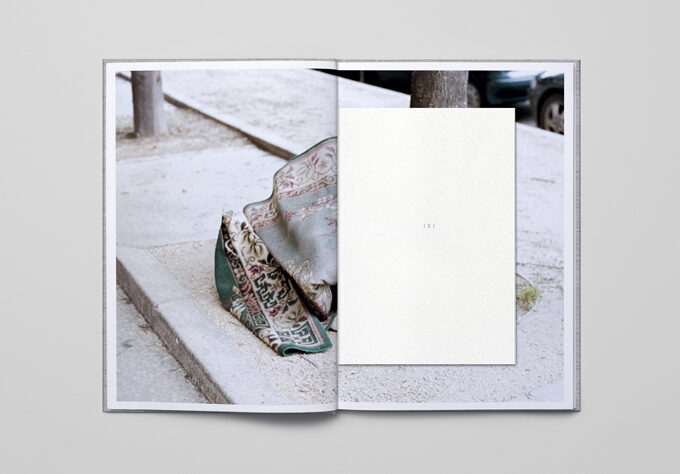

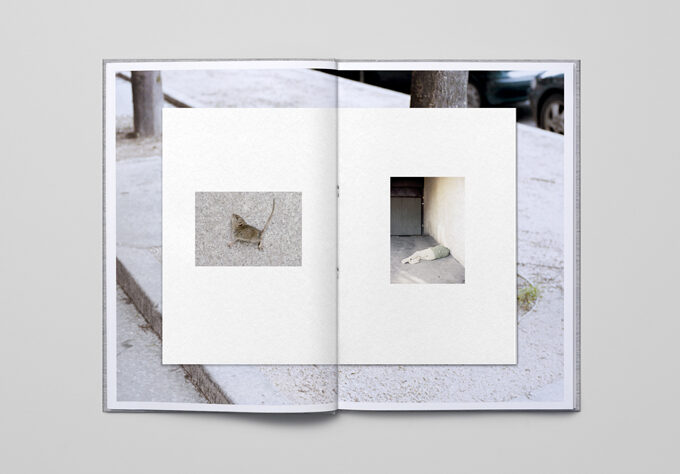

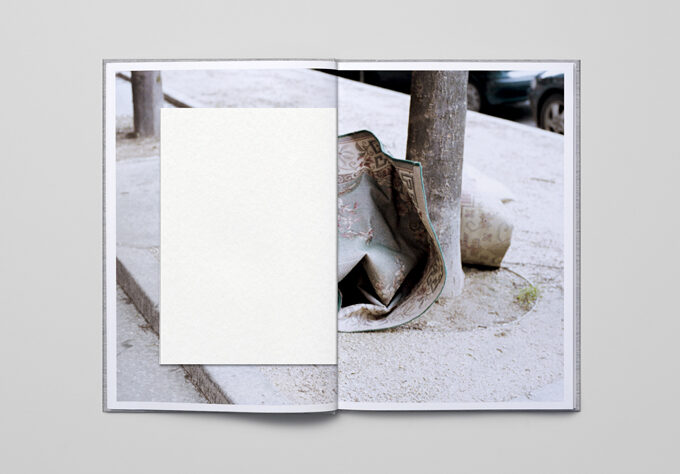

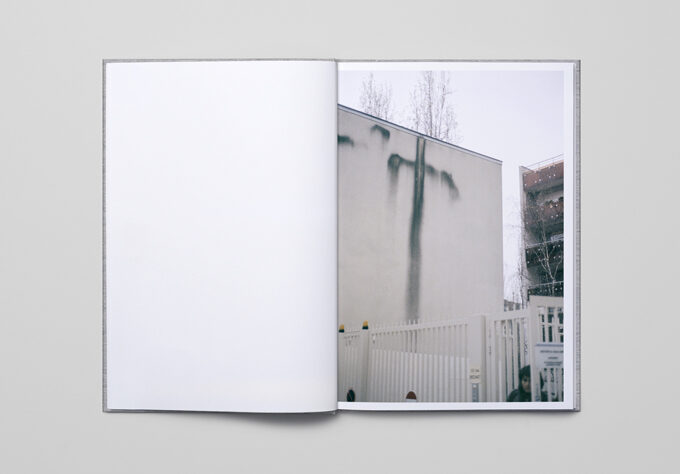

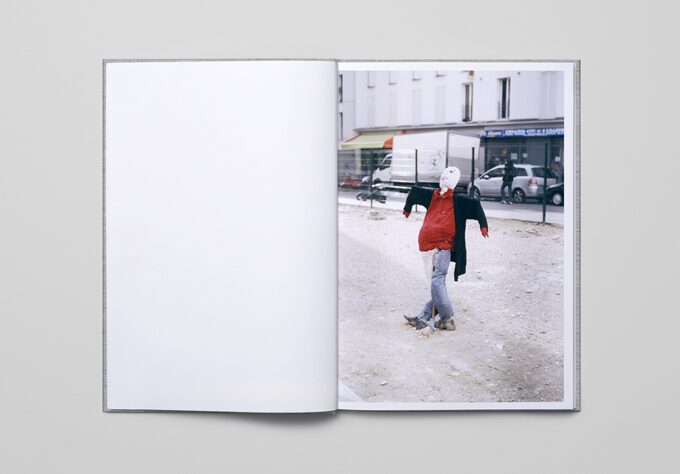

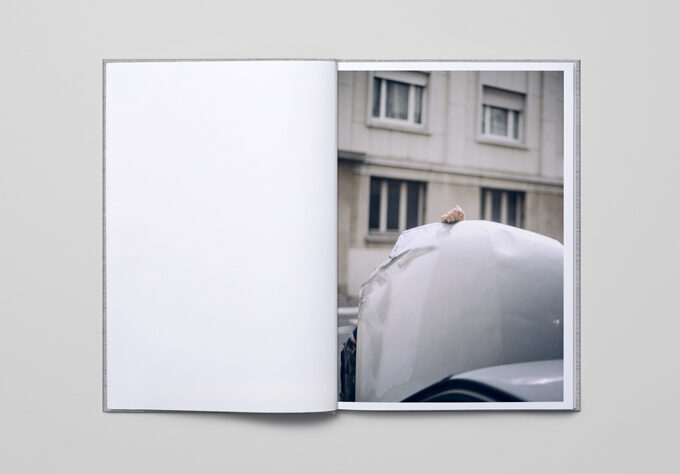

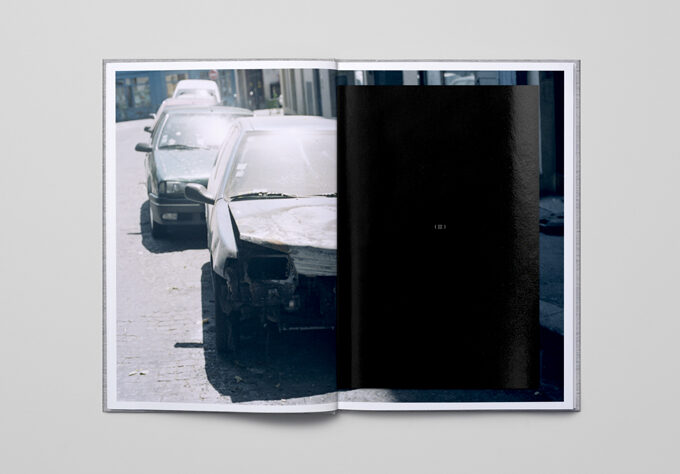

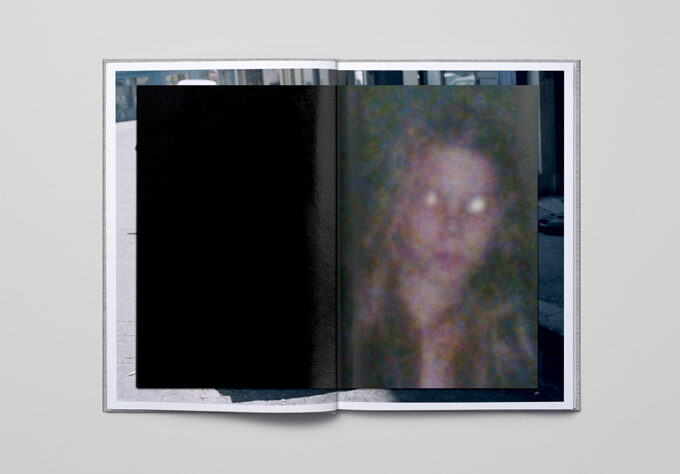

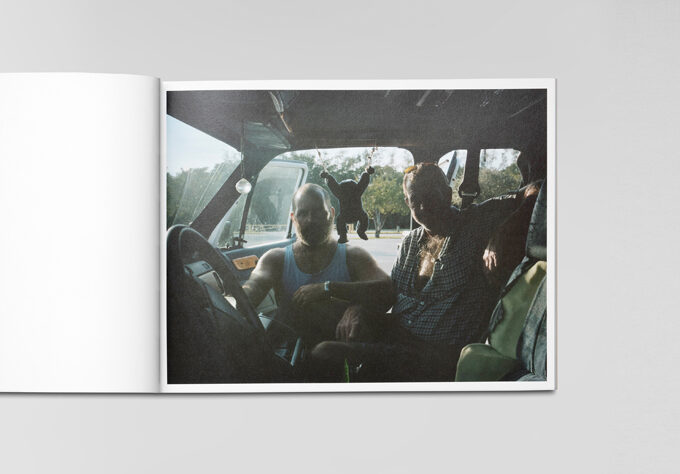

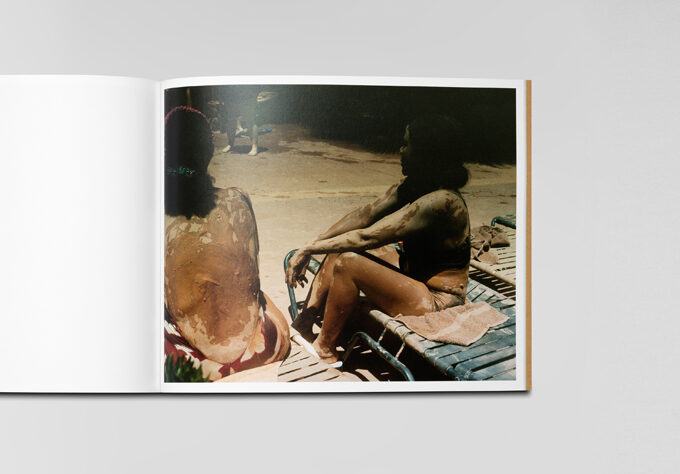

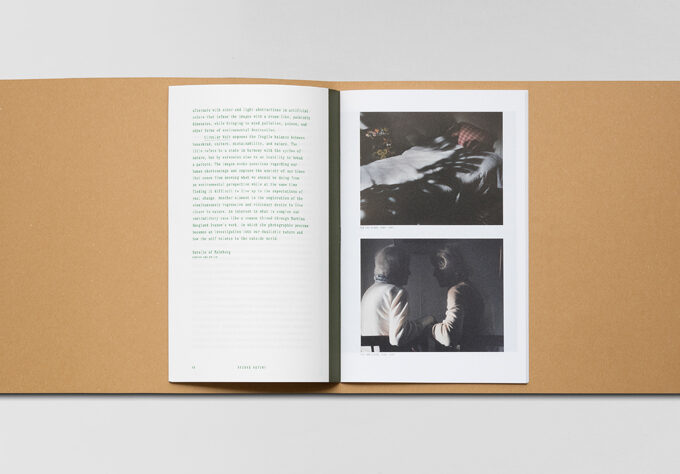

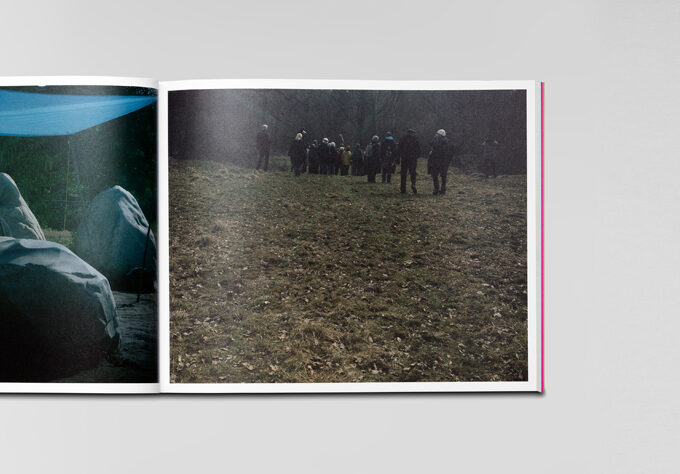

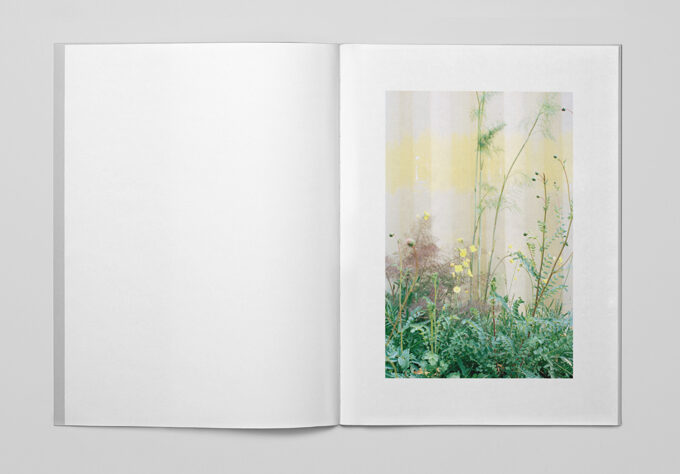

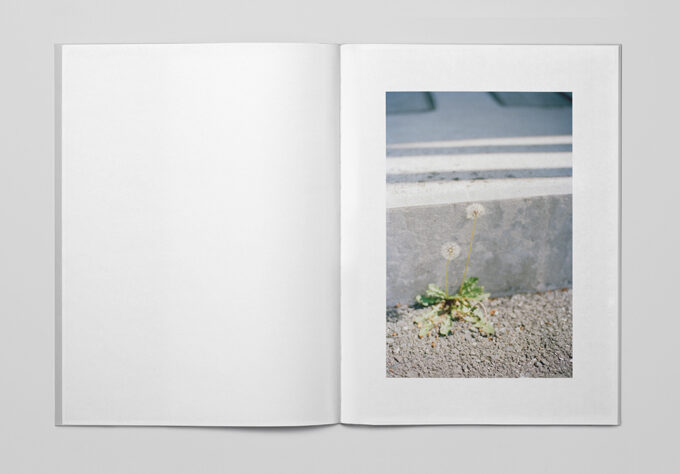

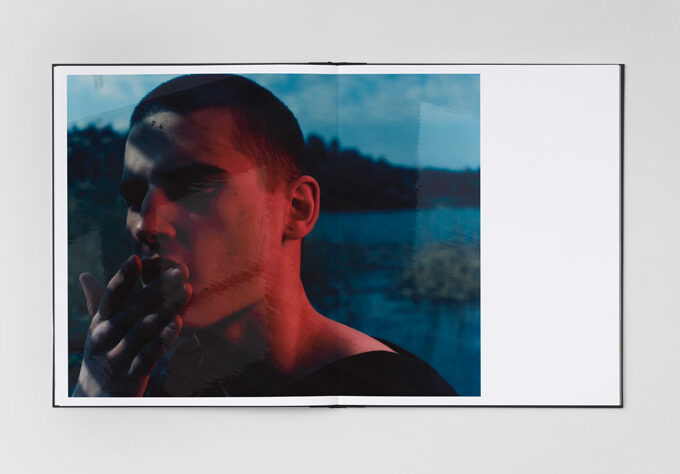

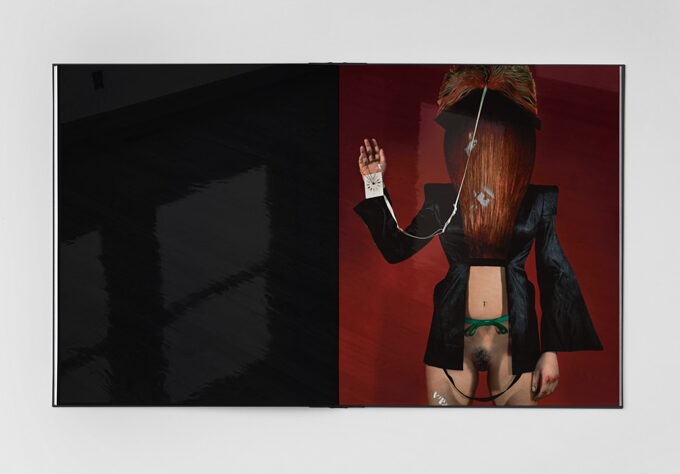

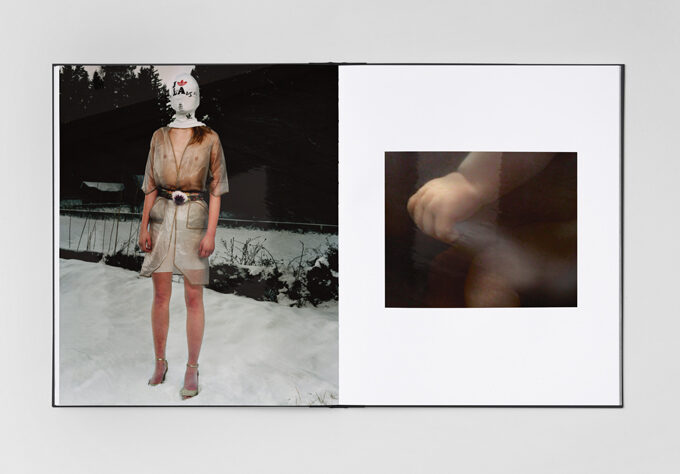

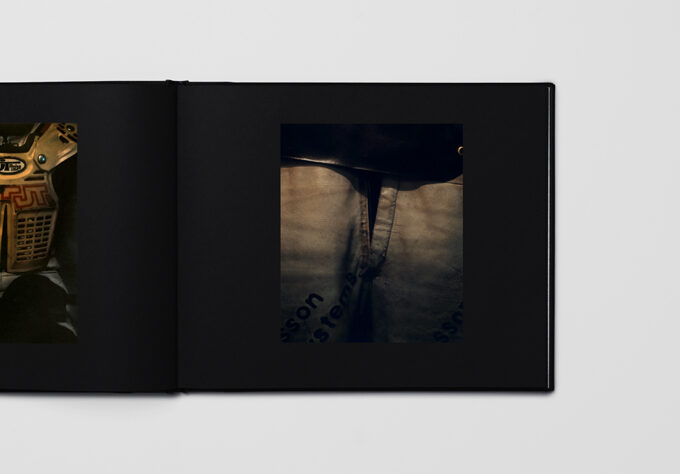

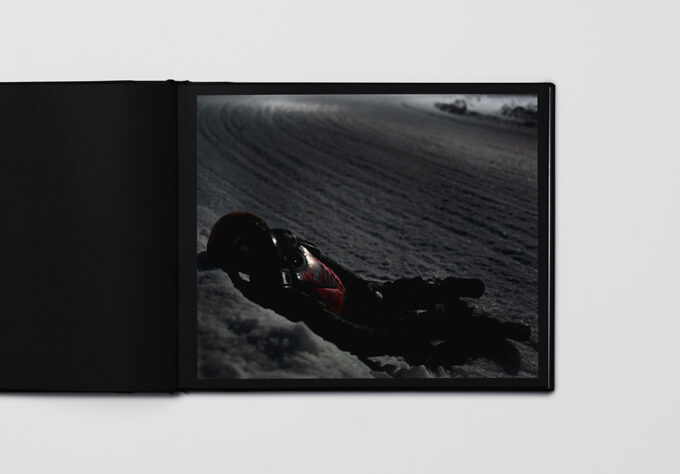

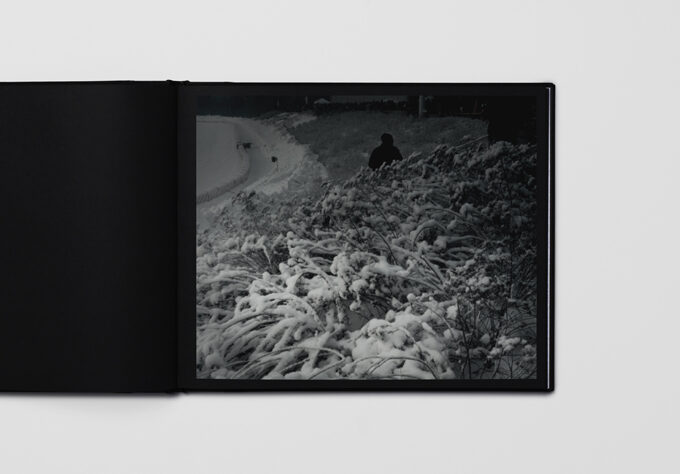

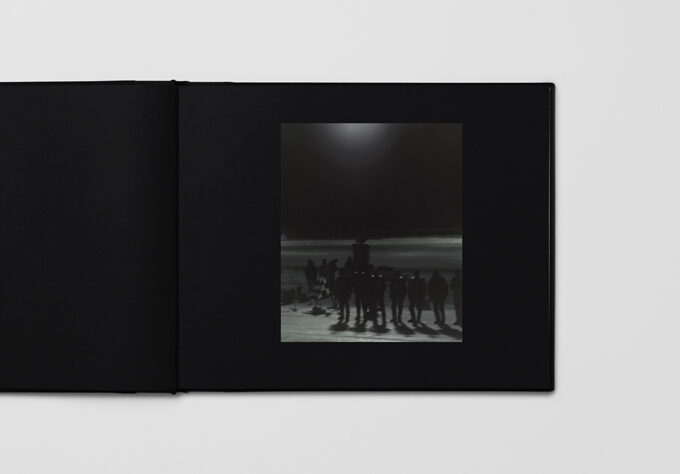

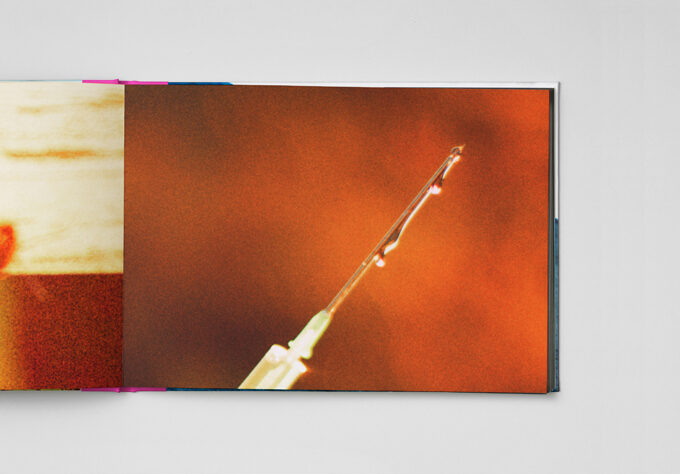

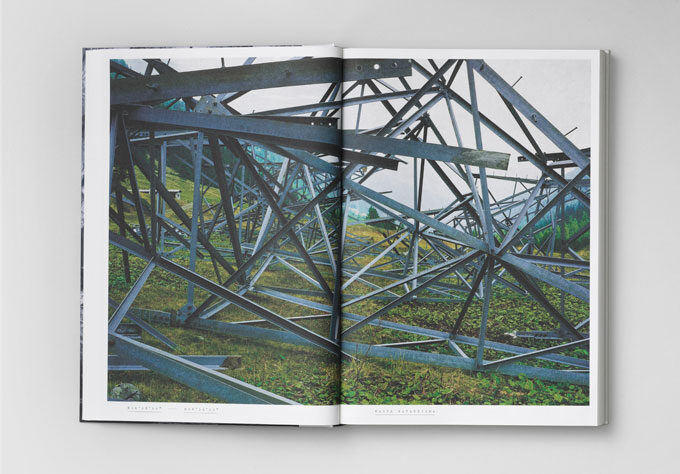

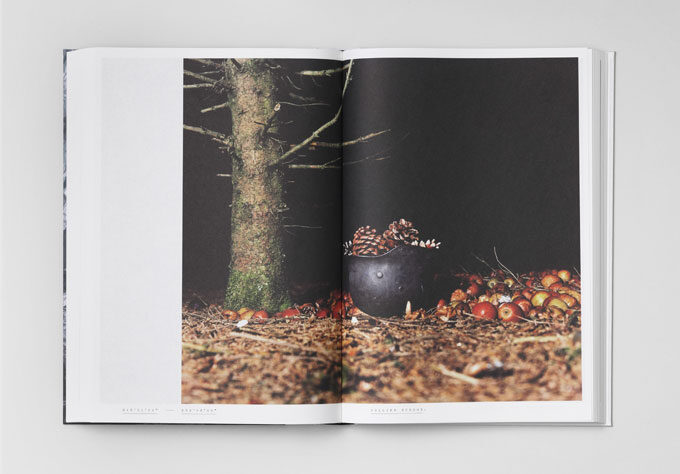

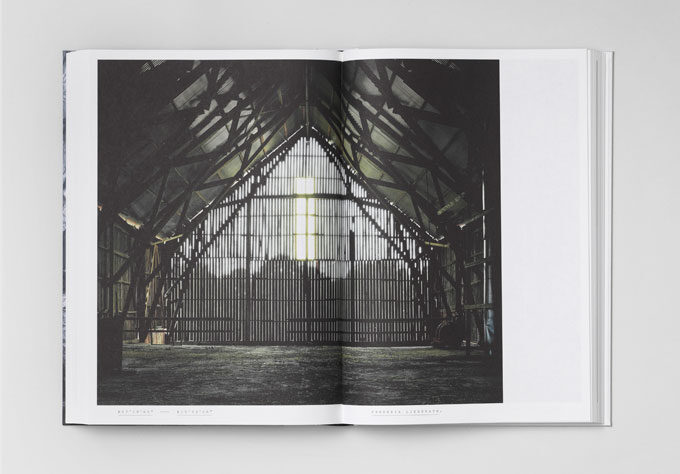

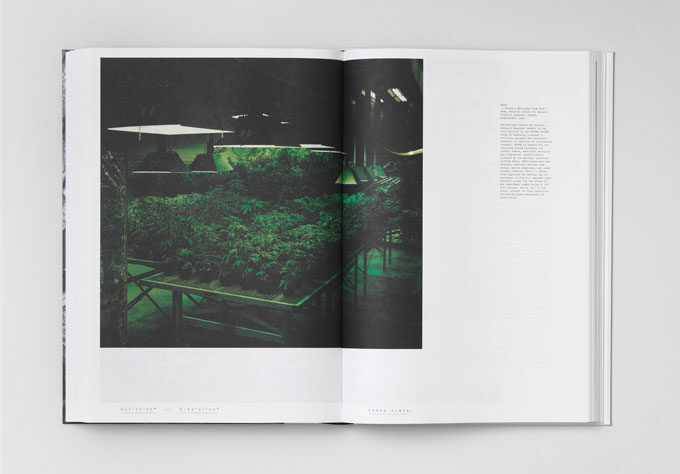

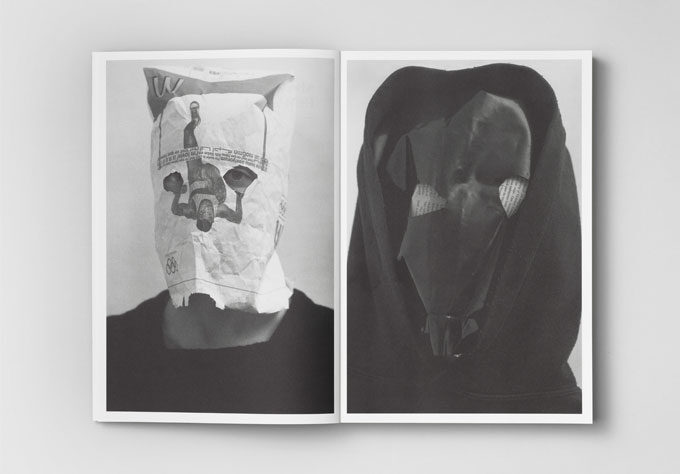

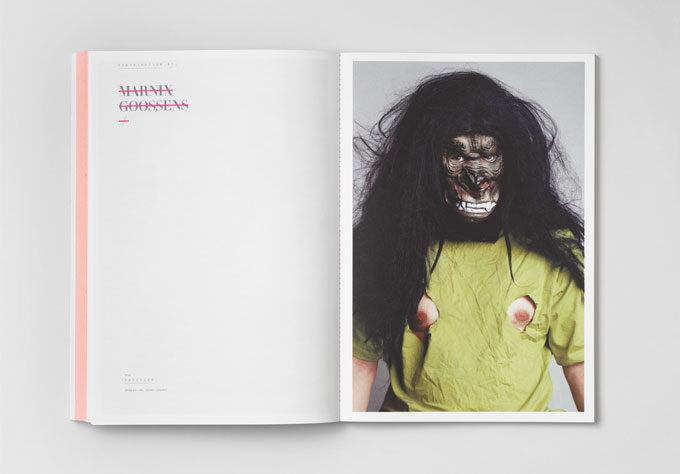

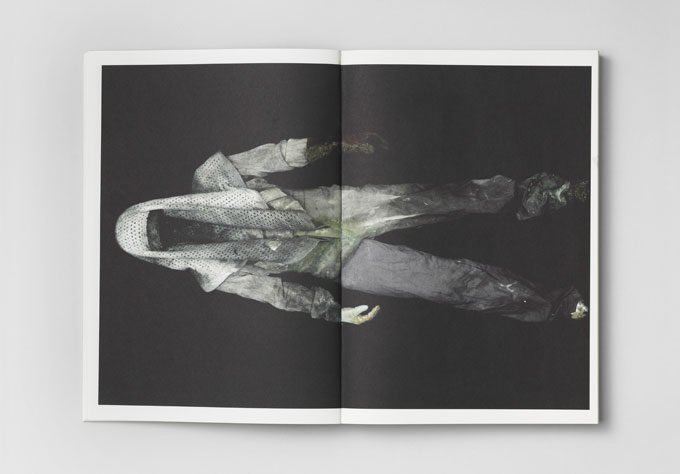

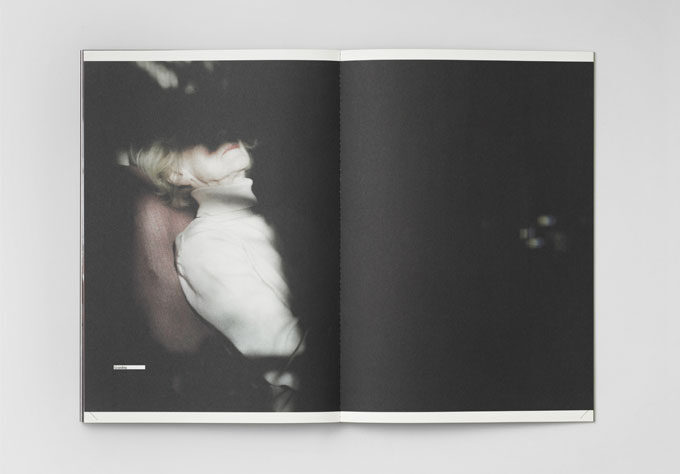

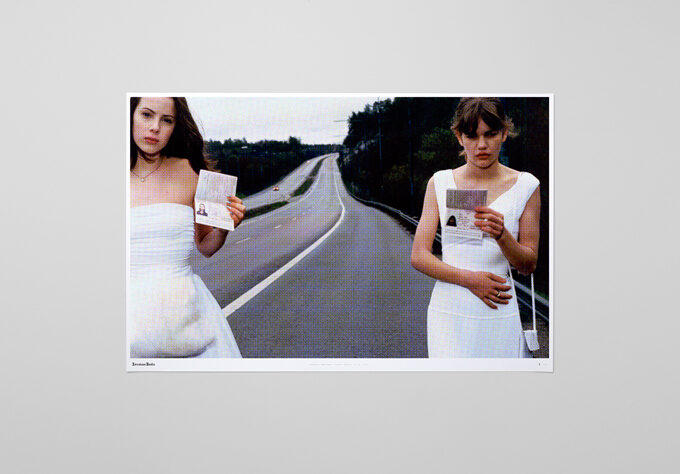

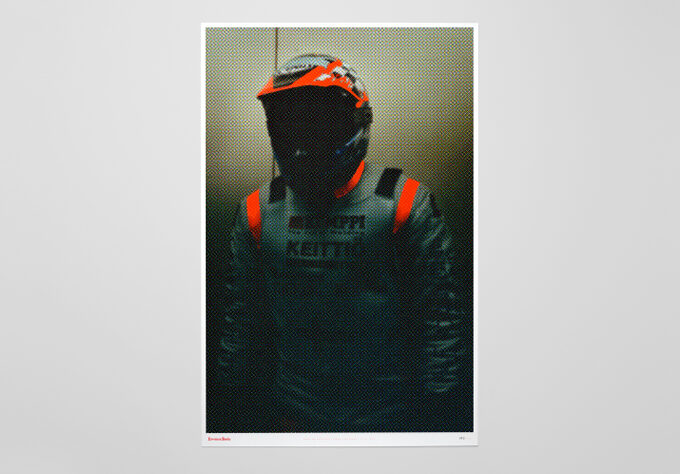

We may encounter these blank or blind spots in any big city. Casually and fleetingly noticing their presence we seldom pay them very much attention. In »Paris« Rindal turns his camera at these spots to get a grasp of what goes on there. What he captures is the daily struggle for survival waged by the city’s poor and fallen — the human collateral chewed up and spat out by the big city machine.

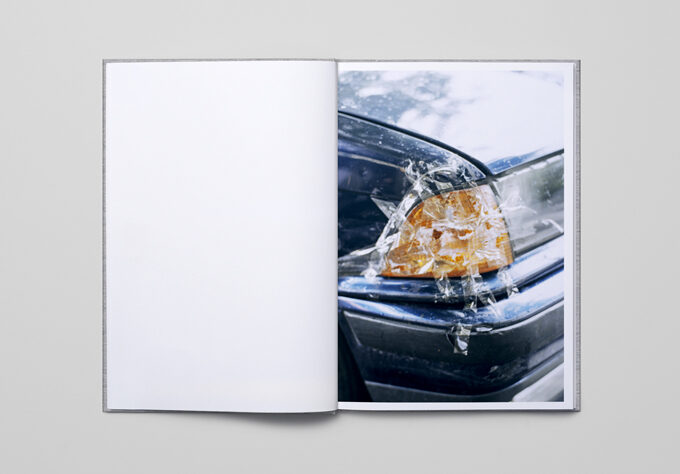

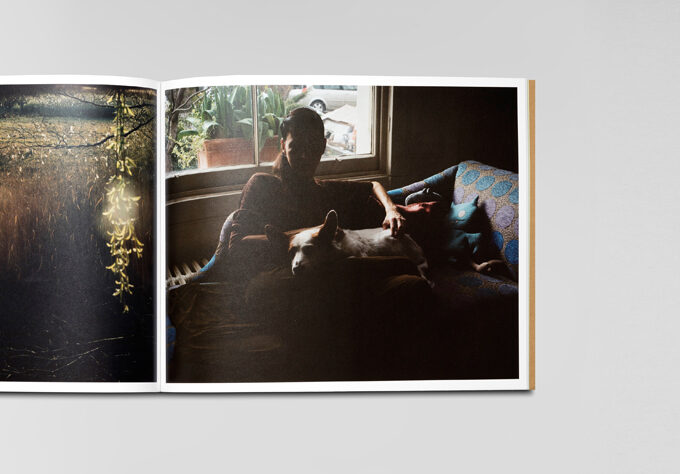

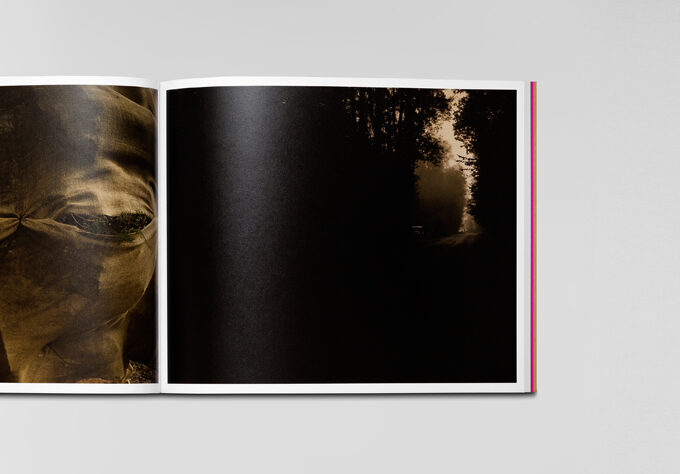

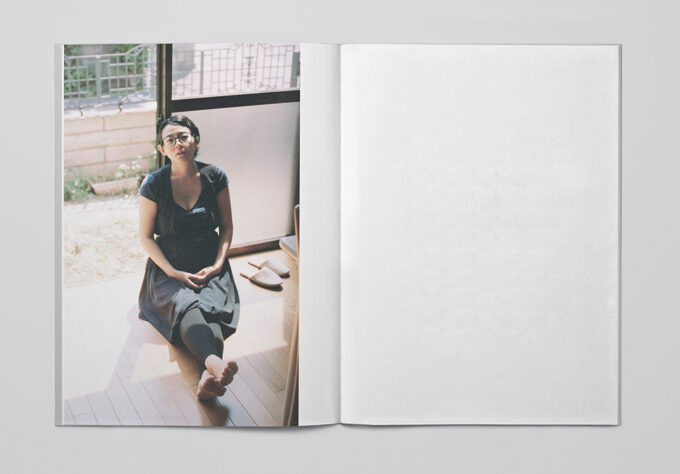

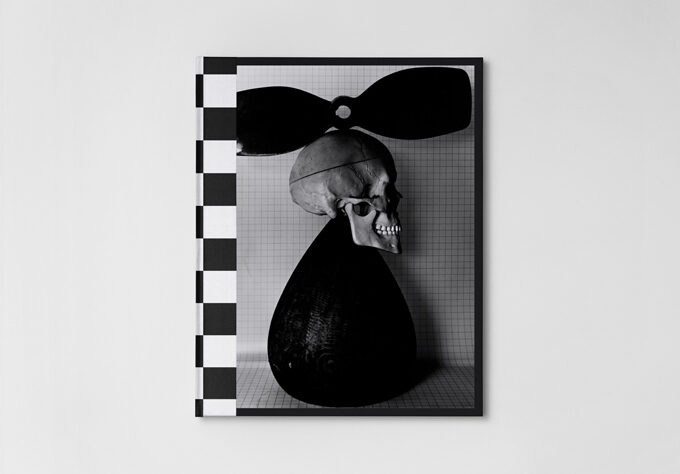

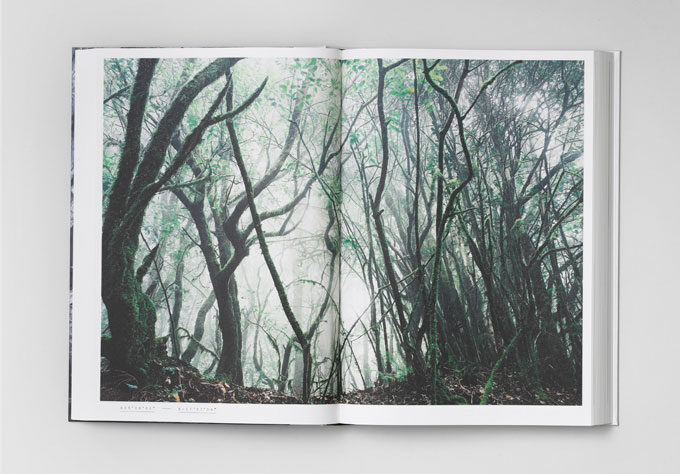

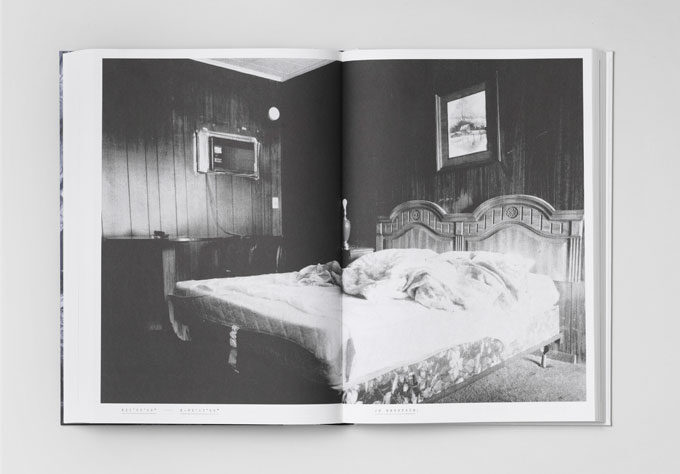

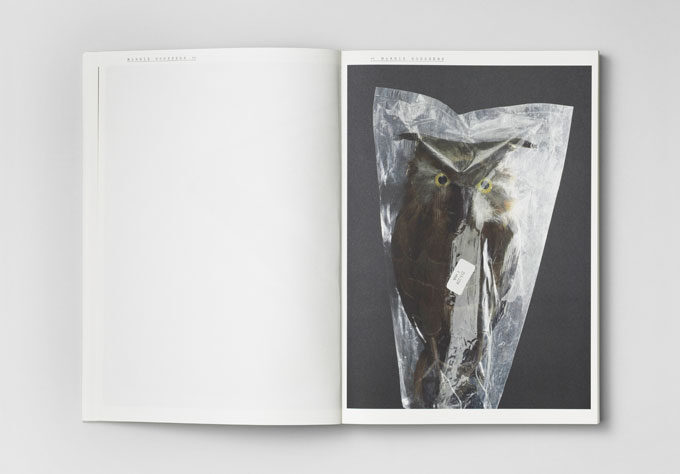

»Paris« is not a socialrealist depiction of street life, however. Like Eugène Atget, the legendary late 19th century photographer of Paris, Rindal approaches his subject in a way that perhaps best is described as forensic. His gaze is naturally drawn to the things, buildings and people that suggest a different physiognomy of Paris than the one we have become accustomed to. Homing in on cracks and fissures in his surroundings his depiction hints at the presence of violent forces beneath the city’s civilized surface.

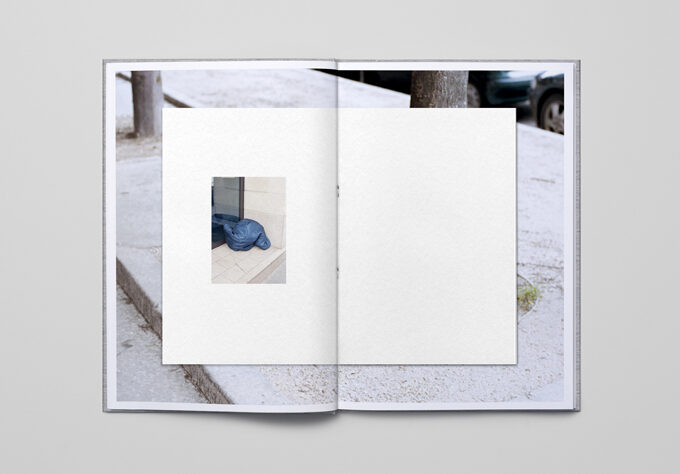

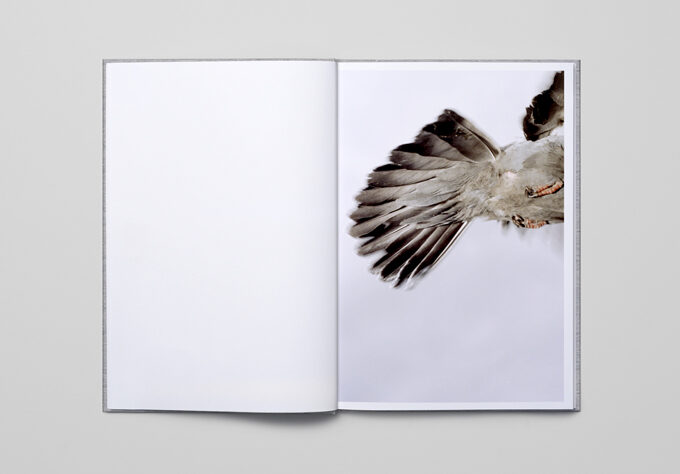

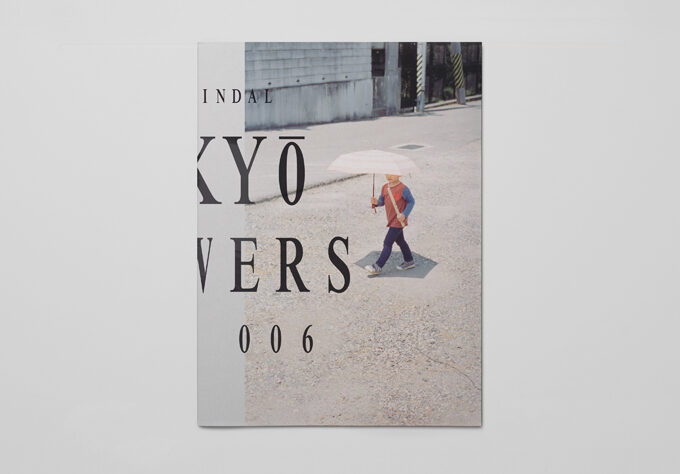

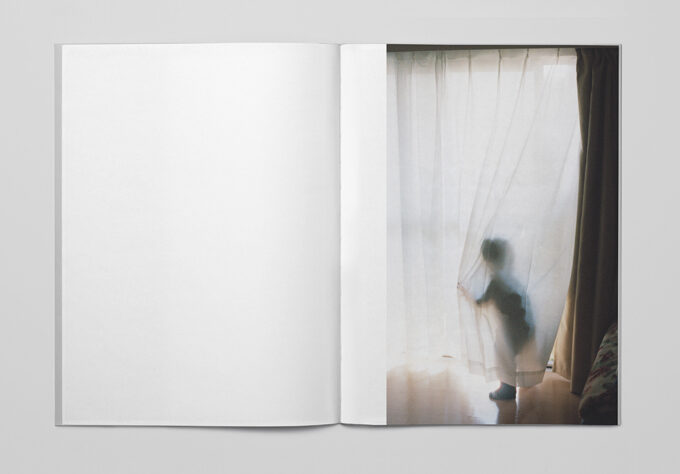

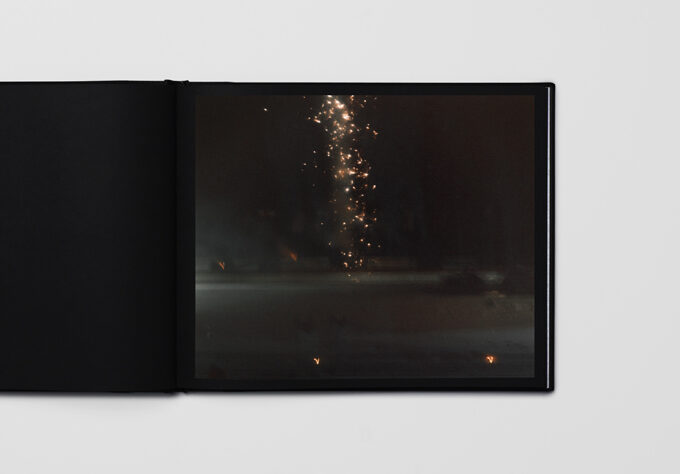

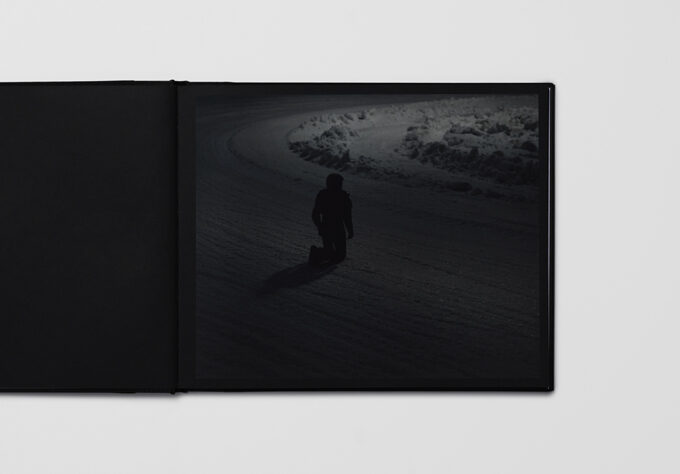

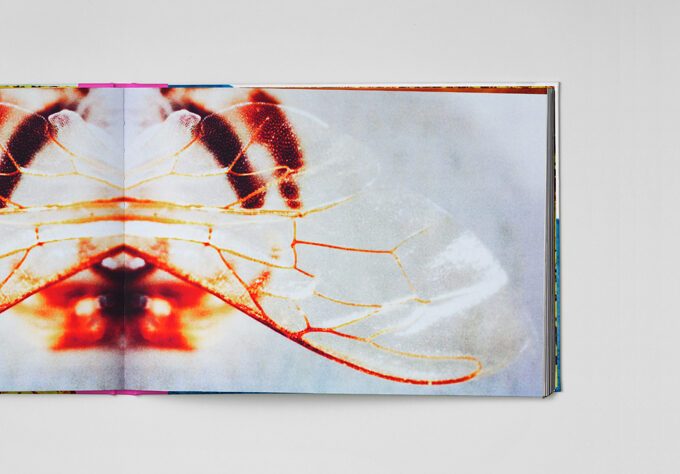

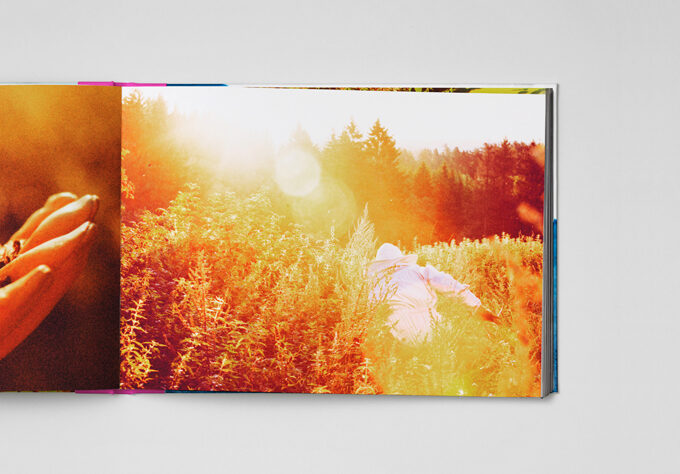

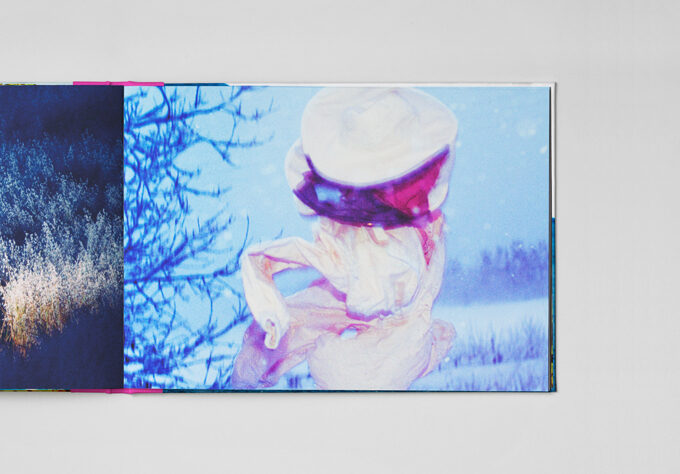

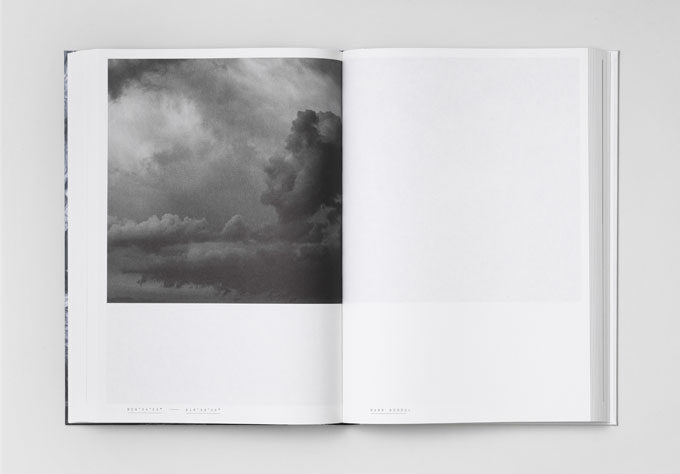

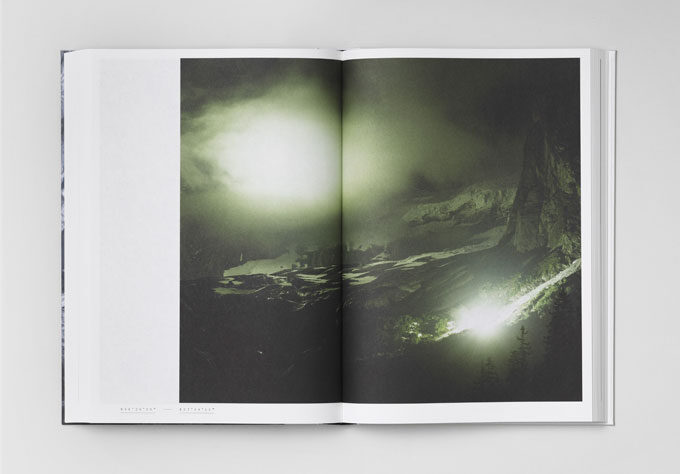

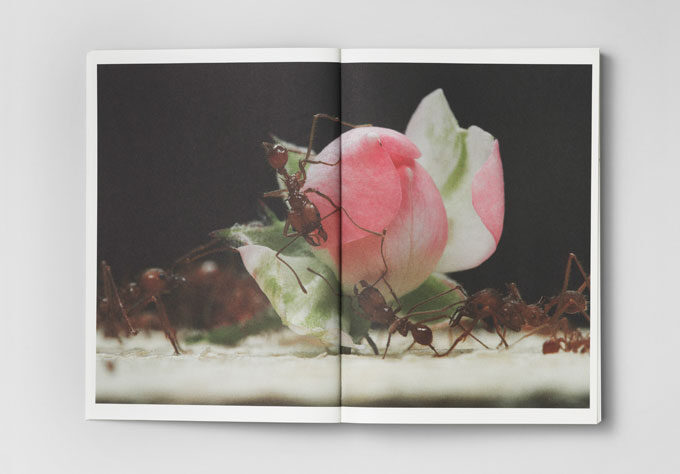

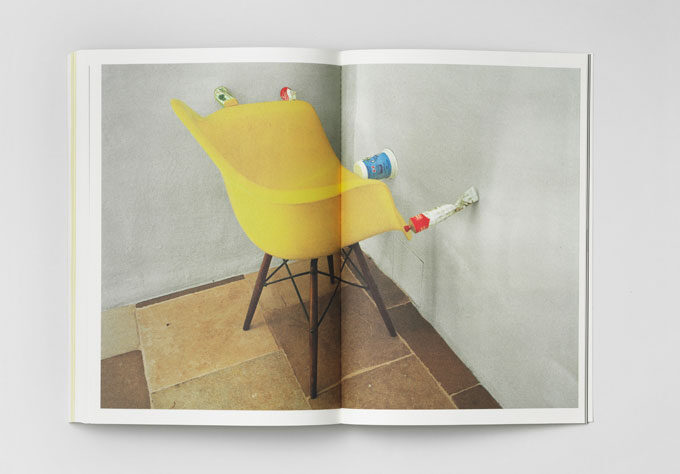

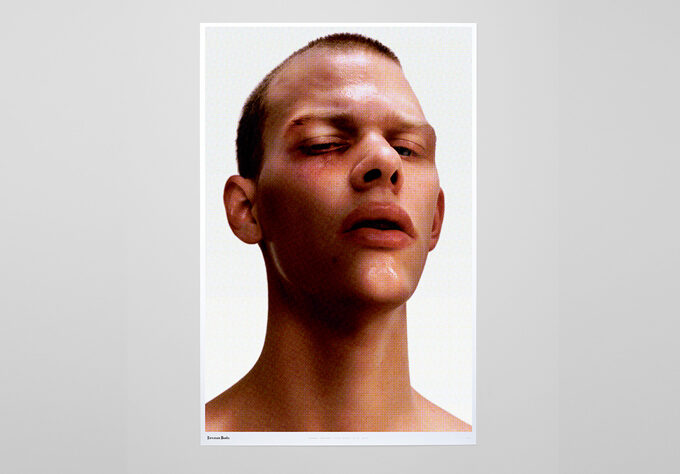

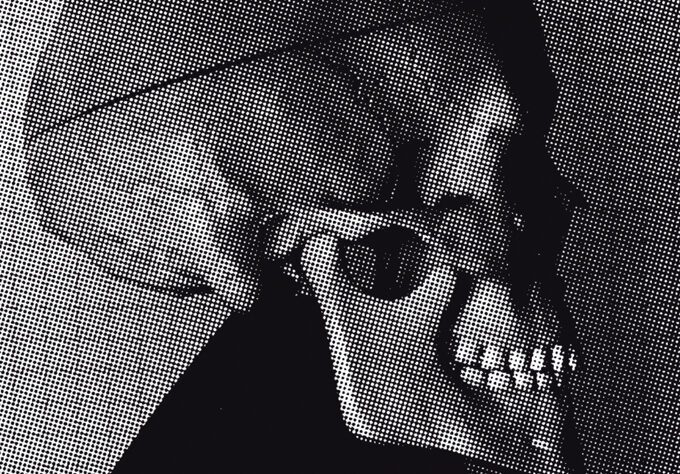

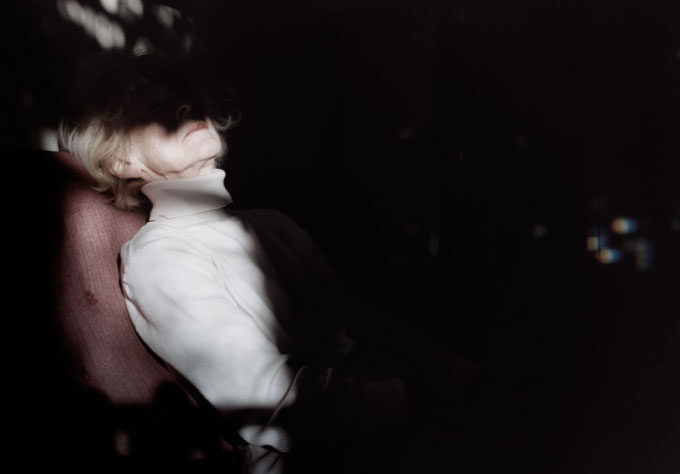

Many of the images in »Paris« evoke the sense of vulnerability that may overcome us when walking urban streets. This feeling of being exposed to an unpredictable outside is a recurring motif in Rindal’s overall work. It is present in the dark Parisian alleys of the »Night Light« series and in »Tokyo Flower«, which traced nature’s ability to survive on Tokyo’s concrete pavements. Here the outside is the broken, sometimes harsh urban reality that defines life for many people. At the same time these images contain what Walter Benjamin called »sparks of contingency« that grant them an urgent poetic quality.

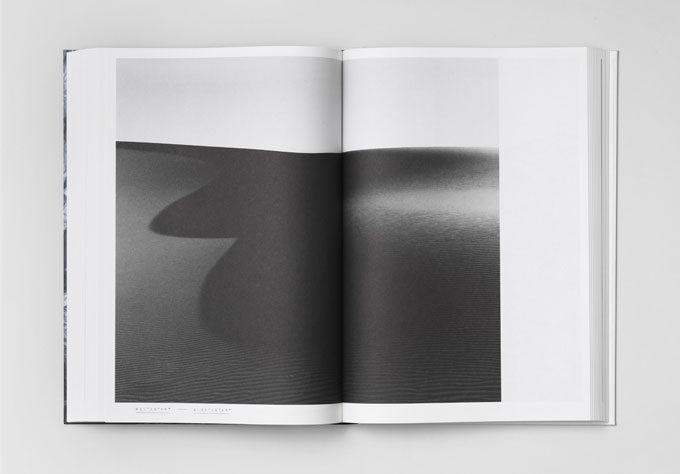

Each image in the »Paris« series lends, in its own singular way, a language to that which is without means of expression. Whether we are witnessing a sleeping homeless man or a discarded building, their existence is calmly acknowledged as something that creates a crack in a city’s idealised image of itself. If there is a moral in these images it might be: the interspaces of our concrete jungle are populated by neglected people, and we look away because deep down we fear that one day we could be one of them.